"The Unraveling Archive. Essays on Sylvia Plath edited by Anita Helle" – Review by Anna Kérchy

Anna Kérchy is a Senior Assistant Professor at the Institute of English and American Studies, University of Szeged, Hungary. She has a PhD in Literature from Szeged University and a DEA in Semiology from Université Paris 7. E-mail: akerchy@hotmail.com

The Unraveling Archive. Essays on Sylvia Plath

The Unraveling Archive. Essays on Sylvia Plath

Edited by Anita Helle

Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2007

paperback, 277 pages, $24.95

ISBN13: 9780472069279

ISBN10: 0472069276

The Unraveling Archive. Essays on Sylvia Plath edited by Anita Helle undertakes the challenging task of shedding new light on Sylvia Plath’s creative work and life based on an abundance of recently discovered material found in various literary, cultural, and personal archives. A study of the Plath corpus necessarily intertwines archeological research with a necrophiliac fascination. The oeuvre is in fact an incomplete oeuvre-in-becoming since the textual corpus believed to be ‘authentic’ is still in the process of being circumscribed as it is gradually ‘regained’ from the careful editing (or caring censorship) of family members, who have been intent on preserving a ‘certain memory’ of their beloved Sylvia. On the other hand, the textual corpus attributed to a confessional poetic voice is regarded as inseparable from the author’s life, her mythified struggle with the incompatible femininity positions (artist, poet-rival / wife, mother), and most significantly her tragic death, the suicidal authorial persona imposed on Plath (that unforgettable iconic freeze frame image of her fragile body lying on the kitchen floor with her head resting in the domestic gas chamber of the oven). Accordingly, the blurb on the collection’s back cover explicitly draws on the fresh attention raised by posthumous (re-)publications (such as Plath’s Unabridged Journals edited by Karen V. Kukil, a “restored edition” of her Ariel poems edited by Frieda Hughes, and Ted Hughes’s Birthday Letters), which promised to re-evaluate Plath’s canonical and critical location by virtue of revealing yet unknown (auto)biographical aspects.

However, as Helle convincingly explains in her introduction entitled “Archival Matters”, archives set up for individual authors include more than terminally ordered deposits that compensate for the decay of the literal body: they also contain the discursive transactions surrounding them. Therefore, archives can also contribute to the work of demythologization as they necessarily decompose in the sense that processes of dissemination and modes of retrieval reconfigure the hierarchical field of what is to be valued. Moreover, since they function as the “repositories of embodied memory”, archives span beyond official institutions: mélange-like, they include (re)collections of disparate media and styles (from images piled up on the Internet to voice recordings and personal memories). One of the greatest achievements of The Unraveling Archive is that it ambitiously aims at reflecting on the totality of the self-disseminating archive: besides meticulously analyzing prominent pieces of Plath’s original artwork, housed at such major institutionalized literary archives as Smith College, Indiana University, and Emory University, the volume also pays attention to the archival surplus, rediscovering the usefulness of the peripheral detail, understudied juvenilia, histories of sound and silence, of fragment and palimpsest “as tools for critical incision”. Thus, the volume traces a methodological pathway as well: Helle’s wonderfully phrased introduction encourages researchers to interpret archives in the model of collage composition, in terms of narrative and encounter, with the aim of undoing “the myth of monolithic memory”.

The collection signifies an important contribution to Plath studies by capturing its very transition, the scholarship’s turn toward historiographic textual and material research. The essays revise and complement canonized knowledge by re-evaluating old representations of Plath, introducing new questions and methodologies, and enriching the contexts of her writings by unraveling tangled connections of “histories, temporalities, narratives, contingencies”. Besides the primary aim of rejecting totalizing narratives of suicidal extremity, the chapters pursue exciting trajectories: they expand our understanding of the political contexts of Plath’s postwar writing, broaden the 20th-century cultural and interdisciplinary contexts to which her work belongs, elaborate problems of textual editing and criticism, and reconsider Plath’s intertextual debts to her contemporaries.

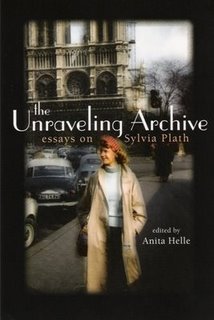

The beautiful photograph on the front cover perfectly illustrates the volume’s innovative intention to de-/recontextualize Plath: instead of salon belle, disciplined society lady, wife of a poet laureate, or neurotic artist, we see Plath as a smiling tourist, on the road, just passing the Cathedral Notre Dame and the red lights of a traffic signal, thoughtfully wandering in an unfamiliar-familiar Parisian space penetrated by a desire for the transcendental (‘the cathedral’) and the transgressive (‘the red lights’) just like her poetry, while she is looking and moving beyond the picture frame, apparently successfully escaping our epistemophiliac gaze and the readerly attempt to enclose her and her art within final meanings. Accordingly, Helle leaves the meaning of this cover photograph from 1956 tellingly open in her study, balancing between decoding it as a “minor incident in accidental tourism”, “a footnote in the history of her visual education”, or a “souvenir of a relationship gone sour”, implicitly leaving space for further interpretations.

The essays are organized under two themes: The Plath Archive aims to outline the corpus and its politics by focusing on newly published, underutilized, and underrepresented material, while Culture and the Politics of Memory discusses the expansion of critical approaches to Plath and the “explosion of the canon” with a “heightened awareness of the contexts and settings that have mediated our understanding of Plath’s multiple identities”.

In the first part, Tracy Brain’s “Unstable Manuscripts: The Indeterminacy of the Plath Canon” concentrates on the restored edition of Ariel to allow us a glimpse at the very process of textual composition. Brain reveals the difficult decisions Plath struggled with while writing, editing, and eventually being unable/reluctant to complete her works and points out that the instabilities (optional titles and variations of sequence) might lead to alternative configurations, new meanings, and, potentially, a more empowering image of Plath. Robin Peel’s “The Political Education of Sylvia Plath” calls attention to the poet’s ideological apprenticeship and dialogue with politics through an analysis of her annotations on curricular and extracurricular materials. The essay suggests that the final work’s topoi of “the battle with the Other” and her trademark ghostly, anxious imagery – commonly read along the lines of gender, neurosis, and personal battle – provide explicit references both to a Cold War and nuclear war awareness and to a critical ability to see America better from a global perspective. As curator of a Plath visual arts and manuscripts exhibition, Kathleen Connors not only provides an insider’s view on “Visual Art in the Life of Sylvia Plath” but also complements her essay with two wonderful reproductions of Plath’s original paintings from the 1950s. “Mining riches in the Lilly and the Smith Archives”, Connors traces how juvenile cross-disciplinary painterly experiments affected the visual world of the mature poetry, how a mutual interplay came about between the “eye” and “I”, picturing and composing, the visualized and the verbalized. Kate Moses concentrates on the oral archive in “Sylvia Plath’s Voice, Annotated”: her discussion of audio recordings of Plath’s voice in poetry readings and interviews conducted from 1958 through early 1963, is rounded out with an appendix containing a comprehensive listing of documentable recordings replete with information on their broadcast and commercial releases. Her “close listening” decodes voice as “a problem, a metaphor, a theme, a mode of access to a style” in its multi-layered dimensions.

In the second part, Sandra Gilbert’s “On the Beach with Sylvia Plath” analyzes how a long neglected poem, “Berck Plage”, offers crucial insight into the author’s life, her “death-drenched” work that juxtaposes carnal appetite with timor mortis and medical nightmares, and, more generally, the mid- to late 20th-century elegiac poetry of mourning and lamentation. As Gilbert puts it, “the skeptical resignation with which Plath gives ‘it’ (the coffin, the sky, hope) up” in the end reflects the very public myth of modern death beyond private suicidal extremisms. Ann Keniston’s “The Holocaust Again: Sylvia Plath, Belatedness, and the Limits of Lyric Figure” reveals how the Holocaust poems’ physically removed speakers, chronological disruptions, fragmentary forms, and nearly dissolving tropes or figures connect historical with textual violence to eventually enact reality’s very resistance to representation. The psychoanalytically informed rhetorical interpretation shows that the identification with what trauma victims have suffered is both contrasted and intensified by a sense of unbridgeable distance from this suffering to create a sense of intimate distance in an experience of “postmemory”. Janet Badia’s “The ‘Priestess’ and Her ‘Cult’: Plath’s Confessional Poetics and the Mythology of Women Readers” examines how Plath’s status is inextricably linked to the cultural value of the women who read her and how mutually reinforcing detrimental assumptions intertwine Plath’s iconicized cultural image as mad poetess with the stereotyped image of her female reader as a “death girl”, whose immature (mis)reading is defined symptomatically as a sign or cause of her disorder. Anita Helle’s “Reading Plath Photographs: In and Out of the Museum” undertakes a critical reconsideration of the photographic legacy, looking beyond gendered spectacles and exposures of celebrity culture. The aim is to undo the “preciously private” versus the “vulgarly public” divide and to explore public-private meanings of “image events” in formal exhibitions and family albums, in photos as material texts themselves that supplement linguistic meanings and in writings triggered by photos that subvert visual meanings. Marsha Bryant’s “Ariel’s Kitchen: Plath, Ladies’ Home Journal and the Domestic Surreal” rediscovers a missing page from an alternative archive, exploring the location of the poem “Second Winter” in Ladies’ Home Journal – a medium that gave Plath the largest circulation during her lifetime. A new light is cast on the discursive level of mid-century American domesticity (discursive practices of cookery, advertising, or consumership) in its intersection with Plath’s poetry, which notoriously combines housewifery with the hallucinatory or mechanical surreal, allowing for ambiguous interpretations of banal domestic rituals as gender-related burden, as therapeutic, normalizing space, or as source of inspiration. Lynda K. Bundtzeb’s “Poetic Arson and Sylvia Plath’s ‘Burning the Letters’” and Diane Middlebrook’s “Creative Partnership: Sources for ‘The Rabbit Catcher’” concentrate on Plath and Hughes’s shared archive, tracing mutual poetic influences, contradictory messages, and acts of textual violence and abuse habitual in their “collaborative relationship”. In Bundtzeb’s essay, Hughes’s radical editing of Plath’s manuscript, which aroused the unappeasable critical fury of scholars, is contrasted with recurring acts of sabotage and vandalism perpetrated by Plath against her husband’s work, while the enigmatic significance of “Burning the Letters” is paralleled with the hopeless disordering of the poetic corpus. Middlebrook compares Plath’s “The Rabbit Catcher” with the poem of the same title in Hughes’s Birthday Letters with the aim of examining the private mythological meaning of the ‘rabbit’ in the incessant intimate Plath-Hughes dialogue of coded responses to each other’s poetry. The study traces how fantasies of the Lawrenceian aggressive gamekeeper of her own and his fighting erotic prey affect each other’s creativity.

The exciting essays written by scholars of different generations on both sides of the Atlantic likely invite multiple audiences: professional and lay readers, academics, students and poetry lovers alike can all enjoy how The Unraveling Archive intelligently and inventively uncovers Plath’s work in its complexity, variability, heterogeneity, and playfulness. In my view, the most precious bits of the essays are those that uncover and re-animate the embodied being, the lived experience of the woman writer buried under the body of writings. On reading analyses of Plath’s recordings, we almost hear her embodied voice, the vocalization of the poetic text supplemented by stomachs rumbling in the studio, a high, slightly nasal voice, a deep chuckle. On other occasions, the studies nearly revive the handwriting as it composes the manuscripts on recycled paper (with the other pages inscribed with drafts by the other), attesting to a friction between two bodies, of old and past selves (new poems written on the back of the old Bell Jar manuscript), or of star-crossed lovers (Plath’s ink “bleeding through” the indecipherable hooks of Hughes’s letters) “back talking to each other”.