"Civil Religion in Central and Eastern Europe: An Application of an American Model" by András Máté-Tóth and Gábor Attila Feleky

András Máté-Tóth is Professor of Theology and chair of the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Szeged, Hungary. E-mail: andras.matetoth@gmail.com

Gábor Attila Feleky is currently lecturer and manager of the Religions And Values: Central And Eastern European Research Network program at the Department for the Study of Religion, University of Szeged, Hungary. E-mail: felekyg@rel.u-szeged.hu

1. Introduction

In this article, we describe how Robert N. Bellah’s concept of civil religion can be applied to the societies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and used as a framework in research on social cohesion. In the first part, we provide an overview of the basic dimensions of Bellah’s term and of the criticisms of his concept. In the second part, we present several studies on civil religion from the 1970s to the present day. Afterwards, we elaborate some specific functions of religion in CEE, and show some elements in the contemporary societies of this region, which ultimately can be seen as civil religious elements. In the last part, we demonstrate evidence of the existence of civil religion in CEE, showing results of a survey conducted in Hungary in 2008.

The importance of researching civil religious dimensions in CEE lies in the possible responses to the following question: do transitional societies in this cultural region have sufficient cohesion to fulfill their aims? It can also be found in the answers to the other side of the same question: can traditional religions or civil religion – in whatever forms – have a function in establishing or supporting new ways of common life after a more or less totalitarian dictatorship in CEE? This article is to be considered as one of the first steps in the endeavor to find these answers.

2. Civil religion in the US

2.1. Bellah and civil religion

Robert N. Bellah’s first publication to use the well-known idiom “civil religion” was published in Daedalus, the journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in 1967 – more that 40 years ago – under the title “Civil Religion in America.” In this article, he writes:

While some have argued that Christianity is the national faith, and others that church and synagogue celebrate only the generalized religion of “the American Way of Life,” few have realized that there actually exists alongside of and rather clearly differentiated from the churches an elaborate and well-institutionalized civil religion in America. This article argues not only that there is such a thing, but also that this religion – or perhaps better, this religious dimension – has its own seriousness and integrity and requires the same care in understanding that any other religion does. (1)

Based on important speeches by John F. Kennedy and other US presidents, Bellah argues that the use of the name of God means no direct connection with one specific religious tradition, but represents a role of another kind of religion, which should be called, according to him, civil religion. He ends his article with a focus on the function of the concept of civil religion:

Fortunately, since the American civil religion is not the worship of the American nation but an understanding of the American experience in the light of ultimate and universal reality, the reorganization entailed by such a new situation need not disrupt the American civil religion’s continuity. (21)

With this article, Bellah opened a wide-ranging discussion among scholars in sociology, religion, politics, and theology on the contribution of religion to holding modern society together. The debate has contained three major issues:

- 1. Is religion essential for the coherence of society, and if so, how does this work? (This point refers to a theory by French sociologist Emile Durkheim.) Do the basic values of a society have to be rooted in religion and is religion necessary to teach them and to have them respected by a broad majority?

- 2. Do traditional religions (Christianity and Judaism, in Europe and the US) really play this role in democratic societies, taking into account that

– human rights are rooted in the biblical tradition,

– some denominations (the Roman Catholic Church and major Protestant churches) were opposed to democracy until the end of World War II, and

– the commitment of individuals to denominations is decreasing (at least in Europe)? - 3. How and to what extent can and should a “civil religion” (as postulated by the Swiss-

French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his 1762 standard work “Du contrat social”) take over this role from traditional religions and are there any working examples of this?

2.2. The reception of civil religion theory in the US

Critics of Bellah’s theory argue that it is not civil religion that cements modern societies, but law, rational decision-making processes, social justice, and economic development. In these societies, religion, due to the high level of religious pluralism, cannot but work against integration at the level of the whole society. To avoid this anti-cohesive role and to enable one to find the common denominator, religious content should be reduced to the minimum. Nevertheless, this would necessarily deprive religion of its core substance to such an extent that the use of the word “religion” could not be justified.1

2.2.1. A revised definition by Bellah

The comprehensiveness of Bellah’s idea – the incorporation of social integration, nationalism, and justice – may account for the fact that numerous sociologists, researchers of religion, politicians, and theologians have discussed the thesis. The discussion even 40 years after its original emergence cannot be considered to be a completed process, partly due to Bellah’s own reflections and writings.

In further publications, Bellah backs away from the use of the term “civil religion”. In The Broken Covenant, he states that it is no more than an “empty and broken shell.”

In his analysis of American society in “Meaning and Modernity. America and the World” – published in 2002 – he does not use the term “civil religion” at all.

Moreover, as Yamane notes, in his essential book Habits of the Heart from 1987, he never uses the term “civil religion”; instead, he opts for the form “biblical and republican traditions”, championed in place of “civil religion” as a new and more dynamic conceptual response to the same substantive issues.

Even if the original notion was changed for a more dynamic one, Bellah has not ceased to consider of crucial importance the phenomenon that he first described as civil religion, the phenomenon that must be taken into account in order to understand the dynamics of American society.

2.2.2. Public religion

It must be remarked that by the 1990s another concept began to round out the field once dominated by the term “civil religion”. This was “public religion”. The new term had its focus primarily on the roles of religious institutions and social movements. The function of institutions in American society was analyzed in detail by José Casanova, and the role of movements by Richard Wood. To understand the idiom, it should be noted that according to Benjamin Franklin, public religion means the summary of public morality and virtue, without which the US Constitution would be ineffective for republican life. Public religion also refers to expressions of religious belief and behavior generated by private individuals or in the subcommunities, communities, and associations in the voluntary sector that have a direct bearing on public order. Both ways, the summary of moralities and of faith-based activities in public life are inductive, and thus can be seen as “from-the-bottom-up” proposals, argued by William H. Swatos Jr. and Peter Kivisto.

2.2.3. Further studies on civil religion in the US2

According to Donald Patrick Woolley, shortly after its introduction, Bellah’s thesis became so widely accepted that in the early years of the theory there was practically no demand for empirical studies to prove it. The situation changed in the 1970s with studies by scholars like Michael Thomas, Charles Flippen, and Ronald C. Wimberley.

The first endeavor, argues Woolley, was Thomas and Flippen’s “American Civil Religion: An Empirical Study” that scrutinized 100 newspapers (with a special focus on the editorials) issued on the 1970 Honor America Day weekend, using the method of content analysis. This study did not manage to find evidence for the existence of civil religious elements in these writings.

To fill the gap with empirical evidence, Ronald C. Wimberley and his colleagues came up with a sophisticated way to examine if there really is a set of civil religious beliefs to be found in the US. They created an item list to measure civil and church religious beliefs, and included it in a survey mailed to participants of a Billy Graham crusade (of which 115 completed questionnaires were returned). Several items were based on Bellah’s concept of civil religion, while Wimberley included some items related to the link between Christianity and polity. According to Wimberley, “in the absence of prior examples, a set of civil religious items was created from related literature, consultation, and imagination” (Wimberley et al. 892). The eight civil religious items were the following:

- 1. We should respect a president’s authority since it comes from God.

- 2. National leaders should not only affirm their belief in God, but also their belief in Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord.

- 3. Good Christians aren’t necessarily good patriots.

- 4. God can be known through the experience of the American people.

- 5. The founding fathers created a blessed and unique republic when they gave us the constitution.

- 6. If American government does not support religion, it cannot uphold morality.

- 7. It is a mistake to think that America is God’s chosen nation today.

- 8. To me, the flag of the United States is sacred.

Apart from these, the study contained 15 other items that served to measure religious belief, experiences, and behavior. All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree).

The factor analysis resulted in four, well-separated factors: civil religion, religious belief, religious behavior, and religious experience. The factor loadings of civil religious items for the civil religion factor are as follows:

| Item | Loading for civil religion |

| We should respect the president’s authority since his authority is from God. | 0.64 |

| National leaders should not only affirm their belief in God but also their belief in Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord. | 0.54 |

| Good Christians aren’t necessarily good patriots.* | 0.45 |

| God can be known through the experience of the American people. | 0.43 |

| The founding fathers created a blessed and unique republic when they gave us the constitution. | 0.33 |

| If American government does not support religion, it cannot uphold morality. | 0.31 |

| It is a mistake to think that America is God’s chosen nation today. | 0.22 |

| To me, the flag of the United States is sacred. | 0.14 |

Table 1. Civil religious items used in Wimberley’s first study on civil religion, loading for the civil religion factor (Wimberley et al. 1976).

*Scores for this item were processed so they would load positively with the other seven items in this factor. This was required since – unlike in the case of the other civil religious items – it was disapproval of this statement that showed civil religiosity.

The civil religion factor correlated positively with the other four; nevertheless, it proved to be separate from them. Wimberley managed to prove empirically that the civil religious dimension existed, and he paved the way for empirical studies to come.

Another study from 1978 that James A. Christenson co-authored with Wimberley showed that all segments of the population were highly affected by civil religion, except for college graduates and persons with liberal political (or religious) views, who were slightly less likely to hold civil religious.3

One of the most noteworthy studies on the political implications of civil religion was written by Wimberley and Christenson in 1980 on the 1972 presidential election. They showed that civil religious beliefs may be an even a more appropriate variable to predict the result of an election than political party affiliation.

Using content analysis, Cynthia Toolin investigated presidential inaugural addresses up to 1981. She found that – by using the inventory of civil religion – the speeches are in many ways similar to a cleric’s sermon. She discovered two fundamental themes in the speeches: American destiny under God and International example.

Woolley finds that the early 1990s saw the start of a new period in civil religious studies. The hallmark of this phase is Robert Wuthnow’s theory on the divided civil religion from 1988. According to Wuthnow’s thesis, the rise of the religious right is a sign of the division of American civil religion, since, he argues, it split into a conservative and a liberal part. As the liberalization of mainstream religion sparked the rise of the religious right in the 1960s and 1970s, the process of the liberalization of civil religion had the same effect: it brought about the emergence of a conservative branch and civil religion become fragmented. As Wuthnow puts it:

The civil religion […] has become deeply divided. Like the fractured communities found in our churches, our civil religion no longer unites us around common ideals. Instead of giving voice to a clear image of who we should be, it has become a confusion of tongues. It speaks from competing traditions and offers partial visions of America’s future. (256)

As regards methodology, one of the most important recent civil religious studies was conducted by Donald Patrick Woolley. In his study Perceptions of the Presidency: Civil Religion and the Public’s Assessment of Candidates and Incumbents, carried out under the direction of Wimberley, civil religiosity was examined by using the results of two surveys carried out in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1984 and 1998. These surveys, based on the former work of Wimberley published in his articles in 1976, included the following items:4

- The flag of the United States is a sacred symbol.

- God can be known through the historical experiences of the American people.

- We should respect a president’s authority since it comes from God.

- In this country, people have equal, divinely given rights to life, freedom, and a search for

happiness. - In America, freedom comes from God through our system of government by the people.

A sixth item was only used in the 1984 study:

- The creation of our laws has been guided by God.

Woolley analyzed the 1984 items separately, with six variables for the measurement of civil religion, and he created an indicator from the 1998 items, by simply summarizing them. This was possibly due to the strong consistency of the item battery: Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80.

3. Civil religion and religious symbols in CEE

Although civil religion was first described as an American phenomenon, this clearly does not preclude the possibility of its presence in countries other than the US. Several studies show the applicability of the concept in CEE societies as well, as discussed by Tižik. In the upcoming sections, this article – without attempting to offer a comprehensive description of civil religion in the region – aims at showing that certain elements in contemporary CEE societies can be interpreted as signs of civil religion.

After the regime change in CEE, sociologists observed the re-emergence of several symbols in the societies under transformation that could be analyzed within the theoretical framework of civil religion. In our particular pilot research project, we supposed the existence of a social desire for symbolic entities which would be able to establish new societal cohesion in a time of deep change. In general, scholars of this cultural and political region argue mostly for fundamental diversity and tensions, but we will focus on the other side of the coin, on cohesion according to the Durkheimian paradigm.

3.1. God in political texts

In accordance with the original idea of Bellah with the name of God in political texts and contexts, we would like to stress that the form of oaths of office in several European countries finish with the closing form: So help me God. Just to quote the version from the United Kingdom:

“I, NAME, do swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her heirs and successors, according to law. So help me God.”

This closing form is used by politicians without reference to personal religiosity or belonging to one particular religious tradition. The closing form So help me God can be seen as a ceremonial act to highlight the seriousness of the oath. According to the original Christian interpretation, only God grants the success of human plans. So help me God can also be interpreted as the speaker remembering the cultural heritage influenced by Christianity. This long-held tradition was broken down by atheistic and materialistic power, with heavy oppression of religious life and symbols. After the political and ideological turning point, it seems to be necessary to renew “good old traditions”.

In Hungary, the use of God help me is optional; nevertheless, the majority of the Members of Parliament use it.

In speeches made in the Hungarian Parliament, the word “God” can generally be found in expressions like “God knows”. These idioms have neither a religious nor a political message.

In CEE, inauguration ceremonies also show some civil religious elements. In Ukraine, the President-elect is sworn inside the Ukrainian parliament in Kyiv. He stands at the front of the chamber and reads the oath of office while placing his hand on both the constitution and the Bible (Picture 1).

Picture 1. Inauguration ceremony in Ukraine

In Hungary, The Prime Minister is sworn in in the upper chamber of the Hungarian Parliament. He stands at the front of the chamber and takes his oath with one hand over his heart and the other holding a small corner of the Hungarian flag (Picture 2).

Picture 2. Inauguration ceremony in Hungary

3.2. Religious symbols on banknotes

Tim Unwin and Virginia Hewitt made a noteworthy effort to show how the reconstruction of national identities in CEE after the fall of communism is reflected in pictures and symbols on the banknotes in this region. Although the research had no specific focus on religion, Unwin nobly made the database5 on the banknotes available for further investigations, and thus we were able to analyze their religious content. Our results show that numerous – about 50 – banknotes issued in CEE in the 1990s had images or motifs related to religion. This means an average of around 3, but the distribution is far from being even. While the number is as high as 10 in Croatia, in some countries (even in Poland) no banknotes were issued with these characteristics.

| Country | Number of banknotes with themes related to religion | Symbols related to religion |

| Albania | – | – |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 1 | 1 marka: Portrait of Ivan Franjo Jukic, monk (front) |

| Bulgaria | 2 | 1 lev: Icon of Sveti Ivan Rikski (front), monastery church in Rila (back) / 2 lev: Portrait of the monk Pagisios of Chiliander, Monastery of Mount Athos (front) |

| Croatia | 10 | 1, 5, 10, 25, 100, 500, 1000 dinar: Zagreb cathedral (back) / 10 kuna: Portrait of Bishop Juraj Dobrila (front) / 100 kuna: Church of St. Vitus, Rijeka (back) / 1000 kuna: Zagreb cathedral (back) |

| Czech Republic | 4 | 50 koruna – portrait of St. Agnes of Bohemia, ardent heart with a tear (front), portrait of St. Francis, portrait of St. Clara, interior St. Salvator’s Church (back) / 100 koruna: interior of St. Vitus’ Cathedral (back) / 200 koruna: portrait of Comenius, cleric and thinker (front) / 5000 Koruna: St. Vitus’ Cathedral, Loretto, St. Nicolas’ Church, St. Jacob’s Church |

| Estonia | – | – |

| Hungary | 1 | 10,000 forint: portrait of King St. Stephen (front), religious buildings (back) |

| Latvia | – | – |

| Lithuania | 4 | 1 litas: Church of St. Joseph in Paluse (back) / 2 litas: Portrait of Bishop Motiejus Valančius (front) / 50 litas: Cathedral of Vilnius (back) / 100 litas: The old town of Vilnius with the Church of St. John (back) |

| Macedonia | 7 | 50 denar (1993): St. Panteleimon Monastery, Skopje (back) / 50 denar (1996): stucco from the Church of St. Panteleimon, Skopje (front), Archangel Gabriel from St. Ghiorghi Church, Kurbinova (back) / 100 denar (1993): St. Sofia’s Church, Ohrid (back) / 500 denar (1993): St. Jovan Caneo Monastery, Ohrid (back) / 1000 denar (1996): Madonna Icon from the Church of St. Vrachi-Mali, Ohrid (front), interior of Church of St Sofia, Ohrid (back) / 5000 denar (1996): Mosaic representing the Christian universe (back) / 10,000 denar (1992): St. Sofia’s Church, Ohrid (front) |

| Moldova | 4 | 1 leu: Capriana Monastery (back) / 5 leu: St. Dumitru’s Church, Orhei (back) / 20 leu: Horjauca Monastery (back) / 20 leu: Horbov Monastery (back) |

| Poland | – | – |

| Romania | 4 | 1000 lei (1993): Putna Monastery (back) / 5000 lei (1993): Densus Church (back) / 5000 lei (1998): crucifix (back) / 10,000 lei (1999): Church of Curtea, Arges Monastery (back) |

| Slovakia | 4 | 50 koruna: portrait of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, missionaries (front), medieval church at Dražovce, symbolizing the dawn of Christianity in Slovakia (back) / 100 koruna: Face of the Madonna, from St. Jacob’s Church, Levoča (front), the Church of St. Jacob (back) / 200 koruna: Anton Bernolák, priest and linguist (front), St. Michael’s Church, part of Klarisky church (back) / 1000 koruna: Andrej Hlinka, priest and politician (front), fresco of the Madonna from the Roman Catholic church of Silača, Church of St. Andrew in Ružomberok (back) |

| Slovenia | 2 | 10 tolar: portrait of Primož Truba, Protestant cleric (front), church of Ursulinska Cerkev, Ljubljana (back) / 10 tolar: two angels (back) |

| Ukraine | 4 | 1 hryvnia: religious motif (back) / 2 hryvnia: Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kyiv (back) / 5 hryvnia: Iliynska Church, Subotiv (back) / 10 hryvnia: Pechersk Lavra Monastery, Kyiv (back) |

Table 2. Banknotes issued in the 1990s, with elements related to religion

3.3. Religious symbols on flags

The flag and coat of arms of the Slovak Republic includes a double cross. This motif originated in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. The symbol, the so-called patriarchal cross, appeared in the Byzantine Empire in huge numbers in the 9th century. While the interpretation of a simple Christian cross is quite unambiguous, there are many explanations for the meaning of the double cross. One of them says that the first horizontal line symbolized the secular power of Byzantine emperors and the other horizontal line their ecclesiastic power. According to another explanation, the first cross represents the death of Jesus Christ and the second cross his resurrection.

4. New societal identity in Hungary: Monuments commemorating historic events and great leaders of the past

After the change of the regime, new identities were created, in the construction of which religious symbols came in handy, such as that of Christian Hungary. Other examples include crowds singing the national anthem at certain public gatherings and parades and the display of the national flag on certain patriotic holidays.

Picture 3. Display of the Hungarian tricolor

Further examples illustrating such featues are, for example, retelling exaggerated, one-sided, and simplified mythologized tales about the Hungarian founding fathers and other great leaders or grand historical events of the past, such as battles and mass migrations. These are also aspects that are also tied to romantic nationalism, like in the case of. Árpád (c. 850–907), the first ruler of Hungary. He was the probable leader of the Magyar (Hungarian) tribe, and the founder of the Árpád Dynasty. Although he is not considered the founder of the Kingdom of Hungary – that was his descendant, Stephen I – he is generally thought of as the forefather of Hungarians and is often affectionately mentioned as “our father Árpád” (Picture 4).

Picture 4. Statue of Árpád

Turul is the mythological bird in the origin myth of the Magyars. In the legends, turul is mentioned at least twice as shaping the fate of the Hungarians: the first time Emese, mother of Álmos, had a dream where a turul appeared, impregnated her, and told her that her child was to be the father of a great nation. The second time, the leader of the Hungarian tribes had a dream where eagles attacked their horses and a turul came and saved them. This dream symbolized that he must move on with his tribe, and when he did, the turul helped them by showing the way that had led them finally to the land that would become Hungary (Picture 5).

Picture 5. Turul statue

In Hungary, the central site of Heroes’ Square, besides being a landmark in Budapest, is also the place for the Millennium Memorial with statues of the leaders of the seven tribes that founded Hungary in the 9th century, along with depictions of other outstanding figures of Hungarian history (Picture 6).

Picture 6. Monument to dead soldiers in Hungary

Imre Nagy (June 7, 1896 – June 16, 1958) was a Hungarian politician, appointed Prime Minister of Hungary on two occasions. Nagy’s second term ended when his non-Soviet-backed government was brought down by the Soviet invasion in the unsuccessful Hungarian Revolution of 1956, resulting in Nagy’s execution on charges of treason two years later (Picture 7).

Picture 7. Statue of Imre Nagy, facing the building of the Hungarian Parliament

5. Measuring civil religion in Hungary

In early 2008, a survey was carried out by the Department of Sociology at the University of Szeged, Hungary. The applied sample (N=2690) can be considered representative for the population of the city of Szeged. In the extensive (19-page-long) questionnaire a civil religious block was included to trace and measure civil religion.

5.1. Working definition of civil religion

For the pilot research project, we developed a working definition of civil religion by applying our knowledge of the most important benefits of civil religion, taking into account its threefold function:

- it integrates the society by involving members in a common past and destiny, usually expressed in ceremonies and myths;

- it legitimates the social order, as well as common societal goals; and

- it mobilizes society’s members to assume common tasks and responsibilities.

The basic idea of the civil religion thesis is that in advanced industrial societies, which are increasingly secular in terms of institutional religions, civil religion (expreswsed, for example, in the celebration of the state or civil society) now serves the same functions as institutional religions used to in prescribing the overall values of society, providing social cohesion, and facilitating emotional expression. In other words, civil religion offers a “functional equivalent” or “functional alternative” to institutional religions, since they meet the same needs within the social system, as Marshall concludes.

Our working definition is the following: civil religion is the cultural pattern that enhances social cohesion, provided that a significant proportion of the society accepts (or even identifies with) its – theoretically not indisputable – theorems and its – historically not unquestionable – symbols, and has a strong, but not absolute affection towards it. Civil religion – in radical contrast to religious traditions – is not dogmatic and universal, but is the contextually peculiar summary of certain characteristics of a given society.

5.2. The item battery

21 items were introduced to trace and measure civil religion: some of them were taken from Wimberley’s studies, while others derived from various sources, taking into account the special characteristics of Hungary and CEE. The elevated number of items served to obtain a whole and clearer picture of what can be considered – at least possibly – cohesive among the population. This reflects our – rather functional – approach to the theme: civil religion is the ensemble of ideas, notions, and beliefs shared by the vast majority of a given population, thus giving a more or less clear point of reference, and enhancing cohesion. The items were put as statements with the introductory sentence: “Please say whether you agree with the following – religion-related – statements.” The available valid answers were “yes” and “no”. The statements – in order of their acceptance reflective of the proportion of the positive answers – are the following:

| Statement | Proportion of “yes” answers |

| National symbols should be respected. | 97% |

| To me, the flag of Hungary is sacred.* | 89% |

| The world would be better if everyone kept the Commandments. | 81% |

| Only those who have achieved a certain social position through hard work should participate in decision-making and discussions about the country. | 78% |

| Nation is the most important community. | 77% |

| Hungary has always been a Christian country. | 76% |

| Defending the religious traditions of the country is a duty of the government. | 73% |

| Churches and religious communities should be maintained through the donations of their adherents. | 62% |

| Giving financial support to churches and congregations is a duty of the state. | 59% |

| Jesus is the savior of the world. | 58% |

| Adam and Eve existed. | 51% |

| Nowadays, religious values are being attacked in Hungary. | 50% |

| Satan exists. | 41% |

| Good Christians are good patriots.* | 34% |

| It is the right thing for politicians to swear on the Bible. | 32% |

| The leaders of the world should believe not only in God, but also in Jesus Christ.* | 28% |

| A Christian votes for a Christian party. | 23% |

| When it comes to politics, all Christians should think the same way. | 21% |

| If politicians don’t believe in God, they can’t be of good moral character. | 20% |

| For Christians, the market economy is unacceptable. | 20% |

| The authority of the highest leader of the state is from God.* | 9% |

Table 3:. Applied items, in order of acceptance

*Similar items were used in Wimberley’s studies.

The acceptance rate ranges from 9% to 97%, suggesting an explicitly varied perception of the statements. If the proportion of acknowledgement is higher than 30% or lower than 70%, no possible adhesive function can be attributed to the statements, since neither agreement nor rejection is characteristic for the vast majority of the population. The very low level of approvals experienced in several cases suggests that shared rejection may also function as a potential bond.

5.3. Factor analysis

The considerable number of items as well as the diffuse themes suggested the existence of various factors within the civil religious item battery. The principal component factor analysis discovered four separate factors (Table 4).

| Scale | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Christianity, morality, and politics | • When it comes to politics, all Christians should think the same way. • A Christian votes for a Christian party. • If politicians don’t believe in God, they can’t be of good moral character. • The leaders of the world should believe not only in God, but also in Jesus Christ.* • Good Christians are good patriots.* • The authority of the highest leader of the state is from God.* • It is the right thing for politicians to swear on the Bible. • For Christians, the market economy is unacceptable. |

0.76 |

| Biblicism | • Jesus is the savior of the world. • Satan exists. • Adam and Eve existed. • The world would be better if everyone kept the Commandments. |

0.73 |

| State and religion | • Giving financial support to churches and congregations is a duty of the state. • Churches and religious communities should be maintained through the donations of their adherents.** • Defending the religious traditions of the country is a duty of the government. • Nowadays, religious values are being attacked in Hungary. |

0.57 |

| Nation | • To me, the flag of Hungary is sacred.* • Nation is the most important community. • National symbols should be respected. • Hungary has always been a Christian country. |

0.47 |

Table 4:. Factors within the civil religion item battery (principal component factor analysis, varimax rotation, KMO = 0.852, explained variance: 43.7%) *Similar items were used in Wimberley’s studies. **This was recoded (yes and no interchanged) in order to load positively for this factor.

The factor labeled Christianity, morality, and politics accounts for 22.1% of the total variance, while the explained variance of Biblicism, Nation, and State and religion are 8.1%, 7.5%, and 6.0%, respectively.

The items that pertain to the Nation factor have explicitly the highest proportion of “yes” answers, 85% on the average – ranging from 76% to 97% – showing a firmly high appreciation of the “nation” and its features. Statements concerning State and religion – ranging from 50% to 73% – and Biblicism – ranging from 41% (Satan exists.) to 81% (The world would be better if everyone kept the Commandments.) – show lower acceptance. Lagging behind, we find Christianity, morality, and politics – ranging from 9% to only 34% – calling into question the importance of the nexus between religion (religiosity) and politicians for the population, on the one hand, and showing a quite low perception of religiosity and political views as necessarily close-knit, on the other (Table 5).

| Factors | Proportion of positive answers (mean) |

| Nation | 85% |

| State and religion | 61% |

| Biblicism | 58% |

| Christianity, morality, and politics | 23% |

Table 5. Factors within the civil religion item battery, by acceptance rate

5.4. Comparison with Wimberley’s study – Differences

It is possible to compare with Wimberley’s study (Wimberley et al. 1976) due to the fact that four items were taken from it.

| Item (in Wimberley’s study / in the Szeged Study) |

Loading for civil religion (Wimberley) |

Proportion of “Yes” answers (Szeged Study) |

| We should respect the president’s authority since his authority is from God. / The authority of the highest leader of the state is from God. | 0.64 | 9% |

| National leaders should not only affirm their belief in God, but also their belief in Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord. / The leaders of the world should believe not only in God, but also in Jesus Christ. | 0.54 | 28% |

| Good Christians aren’t necessarily good patriots. / Good Christians are good patriots. | 0.45* | 34% |

| To me, the flag of the United States is sacred. / To me, the flag of Hungary is sacred. | 0.14 | 89% |

Table 6:. Common items in the study of Wimberley and Christensen and the Szeged Study 2008 *Scores for this item were recoded, thus the loading marked here can be conceived as an indicator for the hypothetical Good Christians are necessarily good patriots.

Since the civil religious scale used in the Szeged Study is rather an experimental compilation of possibly civil religious items, thus the loadings of the individual items for the whole item battery were unable to show us how “civil religious” a statement is. Closer to our approach to civil religion (the more a statement was embraced, the more civil religious the respondent was), we applied the (high) acceptance of a statement as a sign of civil religiosity.

The comparison shows that the statements found to be explicitly civil religious in the city of Raleigh have little acceptance in Szeged. In the latter case, only a few think that the leaders of the country should be religious, and only 9% believe that the authority of the highest leader has a divine source. This shows that religion and politics are conceived as two separated worlds in the minds of the people of Szeged. Only one third of the population sees a close nexus between patriotism and being Christian. The cause of the differences may be manifold.

One possible explanation may be the different perception of religion in the two countries, mainly due to historical causes (e.g. religion has been gradually and intentionally discredited since the 18th century in Europe, while a similar process has not been present in the US). Here, we must make two remarks which are of great importance to understanding several relevant differences between American and European societies. First, in the US civil religion is backed by a historical continuity, while in the history of European societies there have been several significant changes (it is enough to think of the European model of secularization). Second, while religious individualism and the role of religion as an engine for the building of the civil society have a long tradition in the US, individualism is frequently considered to function against the authority of religious institutions in CEE. Furthermore, the presence of religious symbols has a nostalgic character in CEE and represents the remains of an ancient, premodern state.

5.5.

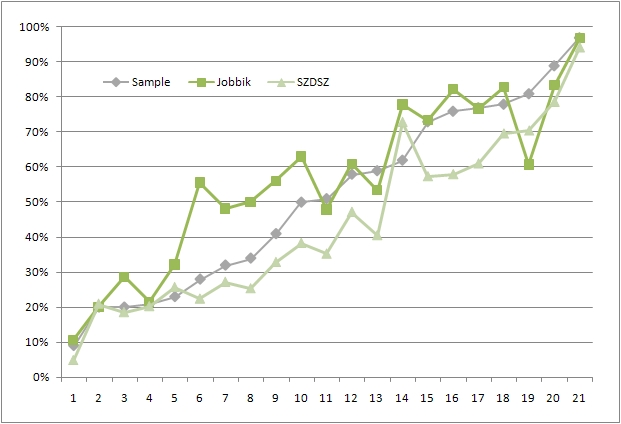

Similarities with Wimberley’s study – Findings affirmed

Since Wimberley and Christenson (1978) found that liberals and college graduates have a lower level of civil religious beliefs, we analyzed how these segments think about these issues. Political views were measured by asking which party the subject would vote for if elections were held within one week. We found that voters for the liberal party (SZDSZ) score lower on civil religious items while those close to Jobbik, a radical right-wing party, are more civil religious. The acceptance of the statements (the proportion of yes answers) of the civil religious item battery was 8% lower than the mean for the whole sample in the case of SZDSZ voters, and 5% higher in the case of Jobbik voters. Nevertheless, it is clear that a lower proportion of approval of an item among the liberals corresponds to a lower proportion of approval among radical right-wing party voters as well. The data-row that derives from acceptance rates of the 21 items among SZDSZ voters correlates almost perfectly to the same index for Jobbik voters (Pearson correlation: 0.90).

Graph 1. Acceptance of civil religious statements among SZDSZ voters

The acceptance rates of the following statements among SZDSZ voters differ most significantly from those of the whole sample:

| Items | Sample | SZDSZ voters | diff. |

| Giving financial support to churches and congregations is a duty of the state. | 59% | 40% | -19% |

| Hungary has always been a Christian country. | 76% | 58% | -18% |

| Nation is the most important community. | 77% | 61% | -16% |

| Adam and Eve existed. | 51% | 35% | -16% |

| Defending the religious traditions of the country is a duty of the government. | 73% | 57% | -16% |

Table 7: . Statements with lowest relative acceptance (compared to the sample) among SZDSZ voters

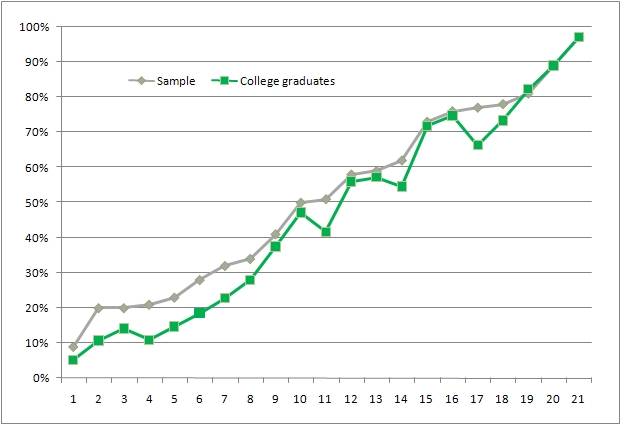

As regards college graduates, one can also experience a lower level of civil religiosity (the acceptance rate was 5 % lower than the mean for the whole sample) – just as was expected. This notwithstanding, the relative acceptance among statements is quite similar to that of the whole sample (see Graph 2).

Graph 2.: Acceptance of civil religious statements among college or university graduates

The acceptance rates of the following statements among college graduates differ most significantly from those of the whole sample:

| Items | Sample | College graduates | diff. |

| Nation is the most important community. | 77% | 66% | -11% |

| When it comes to politics, all Christians should think the same way. | 21% | 11% | -10% |

| The leaders of the world should believe not only in God, but also in Jesus Christ. | 28% | 18% | -10% |

| Adam and Eve existed. | 51% | 42% | -9% |

| If politicians don’t believe in God, they can’t be of good moral character. | 20% | 11% | -9% |

Table 8.: Statements with the lowest relative acceptance (compared to the sample) among college graduates

Clearly, although our perception of civil religion is different, the finding of Christenson and Wimberley (1978) – that civil religious beliefs are present to a lower extent among the highly educated and the liberal – proved to be valid in Szeged as well.

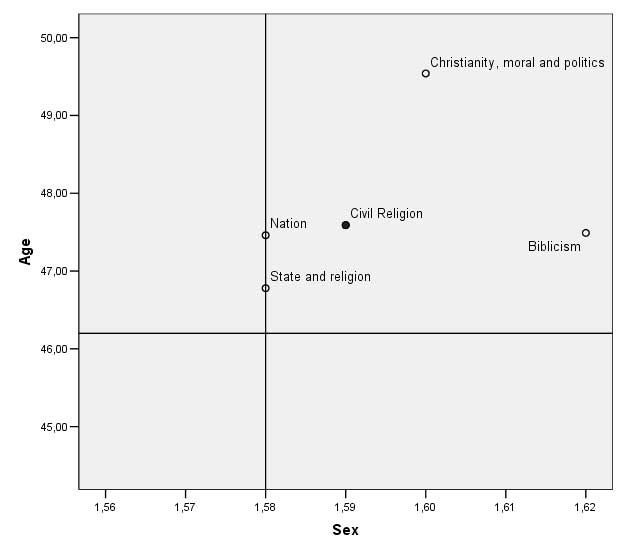

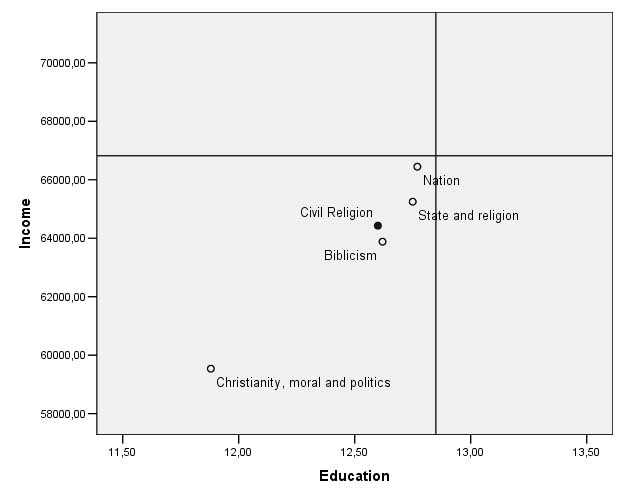

5.6. Sociodemographic characteristics

The analysis of the socio-economic status and demographic features of those that agreed with the statements showed us that we can characteristically experience lower income, lower education, higher age, and a higher female-male index – in comparison with the whole sample (see Graphs 3 and 4). We carried out further analysis into the socio-economic or demographic characteristics of those that embraced statements that pertain to the individual factors. The investigation showed that in these regards significant differences can be found even among the factors, the most obvious one being Christianity, morality, and politics, with those that accepted its statements being the eldest, the least educated, and the worst paid.

Graph 3.: Civil religious factors, by mean of age and sex

The values of the variable „sex” are 1 for men and 2 for women.

Horizontal and vertical lines represent the corresponding means of the sample.

Graph 4:. Civil religious factors, by mean of education and income

Education is measured by years completed in the educational system, e.g. 8=primary school, 12=high-school graduation, 17=university degree)

Income is the per capita monthly income in HUF in the given household.

Horizontal and vertical lines represent the corresponding means of the sample.

5.7. Correlations with religiosity

The item that measures religiosity on a five-point Likert scale (strongly religious, rather religious, religious and not religious at the same time, rather not religious, not religious at all) showed a significant but small positive correlation with the items: 0.17 on the average. Not surprisingly, the highest correlation can be found with the items that pertain to the factor of Biblicism (0.41 on the average). The coefficient is 0.23 in the case of Christianity, morality, and politics, and only 0.12 and 0.06 for State and religion and Nation, respectively.

5.8. Inquiries into the existence of the civil religious block

In search of a possible civil religious block, we examined if the most popular statements of the item list could work as a common denominator for the majority of the population.

Statements accepted by more than 70% of the population (a total of 7 items) were included in the first phase of the inquiry. We found that while 83% of the population affirmed more than 71% of the statements, only 37% agreed with 100% of them.

| Statement | “Yes” answers |

| National symbols should be respected. | 97% |

| To me, the flag of Hungary is sacred. | 89% |

| The world would be better if everyone kept the Commandments. | 81% |

| Only those who have achieved a certain social position through hard work should participate in decision-making and discussions about the country. | 78% |

| Nation is the most important community. | 77% |

| Hungary has always been a Christian country. | 76% |

| Defending the religious traditions of the country is a duty of the government. | 73% |

| “No” answers | |

| The authority of the highest leader of the state is from God. | 91% |

| For Christians, market economy can’t be accepted. | 80% |

| If politicians don’t believe in God, they can’t be of good moral character. | 80% |

| Concerning politics, all Christians should think the same way. | 79% |

| A Christian votes for a Christian party. | 77% |

| The leaders of the world should believe not only in God, but also in Jesus Christ. | 72% |

Table 9.: Most and least popular civil religious statements

In the second phase, we included statements rejected by more than 70% of the population (6 items). 46% of the population disagreed with all the statements and 71% rejected at least 82% of them, and 83% did not agree with at least two thirds of them. We also found that only 10% of the population consistently responded in line with the majority of the population.

Last, we analyzed and benchmarked those that accepted the statements with the highest acceptance rate (“acceptors”) and those that rejected them with a very low proportion of affirmative answers (“rejecters”). The difference in terms of demographic characteristics and SES (Table 10) suggests that overlapping between the groups is not consistent.

| Acceptors | Rejecters | |

| Income (HUF) | 66.352 | 70.092 |

| Age (years) | 47.4 | 45.05 |

| Education (years) | 12.78 | 13.24 |

| Sex* | 1.58 | 1.56 |

Table 10:. Differences between the characteristics of “acceptors” and “rejecters” (means) *The values of the variable „sex” are 1 for men and 2 for women.

76.8% of the sample decided in line with the general opinion at least in 70% of the 13 statements involved, 57.9% did so at least in 80% of the items, and 33.6% in 90% of the statements, while 14% agreed on all “popular” issues and disagreed on all “unpopular” ones. These results show that there is no extensive subsample of people that share the same opinion on the most welcome or rejected civil religious statements.

6. Some conclusions on the way

Even if Bellah’s original concept of civil religion has had to be revised, its application seems to be feasible and fruitful not only in its original environment, but also in the post-socialist, Central and Eastern European context. Studies show that dimensions of civil religion can be found in CEE, the celebratory function of (civil) religious symbols can easily be observed in the region. Nevertheless, when investigating civil religion in CEE, one must consider the cultural background of the region, and the peculiar perception of religion, too. For this reason the operationalization of the concept must take local characteristics into account. We suggest that in analyzing – or even redefining – civil religion, one should stress its potential function of rebuilding and maintaining cohesion in society.

Our study suggests that there are civil religious themes that can unite the majority of a given society in CEE; however, a solid civil religious block cannot be traced. For clearer results, it seems to be necessary to refine the operationalization of the concept. Nevertheless, the presence of civil religion is unquestionable, and deeper research in CEE and comparison with other subregions of Europe could certainly provide a deeper understanding of societies and religion in CEE.

Notes

1 Fenn gives a concise summary of the critics of the notion of civil religion, with a well-elaborated bibliography. R. K. Fenn, “Civil religion,” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Smelser, N. J. et al. (eds.) (Amsterdam, New York: Elsevier, 2001. 1874-78). ↩

2 The description of these studies is largely based on Woolley’s Perceptions of the Presidency: Civil Religion and the Public’s Assessment of Candidates and Incumbents (Woolley, 2008). ↩

3 In a later study, Arnold Beck and Eric Woodrum found that southern blacks are less likely to hold civil religious beliefs than whites. Eric Woodrum and Arnold Bell, “Race, Politics, and Religion in Civil Religion Among Blacks,” Sociological Analysis 49 (1989), 353-367. ↩

4 The values were coded as follows: 1- Strongly Disagree, 2- Disagree, 3- Uncertain, 4- Agree, and 5- Strongly Agree. ↩

5 T. Unwin and V. Hewitt, “Database of Banknotes of Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s.” 2004. Available from Tim Unwin, Royal Holloway, University of London. ↩

Works Cited

- Bellah, Robert N. “Civil Religion in America.” Daedalus 96 (1967): 1-21

- Bellah, Robert N. The Broken Covenant : American Civil Religion in a Time of Trial. New York: Seabury Press, 1975.

- Bellah, Robert N. “Meaning and modernity: America and the World.” Meaning and Modernity: Religion, Polity, and Self. R. Madsen (ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. 255-276.

- Christenson, James A., and Wimberley, Ronald C. “Who is Civil Religious?” Sociological Analysis 39 (1978): 77-83

- Fenn, R. K. “Civil religion.” International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. N. J. Smelser (ed.). Amsterdam, New York: Elsevier, 2004. 1874-1878.

- Marshall, Gordon. A Dictionary of Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Swatos Jr., William H., Kivisto, Peter. Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, Calif.: AltaMira Press, 1998.

- Tižik, Miroslav. “Out off Civil Religion in Slovakia after 1993.” Church and Religious Life in Post-Communist Societies. Révay, E. et al. (eds.). Budapest, Piliscsaba: Loisir, 2007. 223-239.

- Toolin, Cynthia. “American Civil Religion from 1789 to 1981. A Content Analysis of Presidential Inaugural Addresses.” Review of Religious Research 25 (1983): 39-48.

- Unwin, Tim and Hewitt, Virginia. “Reconstructing National Identities. The Banknotes of Central and Eastern Europe in the 1990s.” Crisis and Renewal in 20th Century Banking. Green, E, et al. (eds.). Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. 254-275.

- Wimberley, Ronald C. “Testing the Civil Religion Hypothesis.” Sociological Analysis 37 (1976): 341-352

- Wimberley, Ronald C. and Christenson, James A. “Civil Religion and Church and State.” The Sociological Quarterly 21 (1980): 35–40.

- Wimberley, Ronald C., et al . “The Civil Religious Dimension. Is It There?” Social Forces 54 (1978): 890-900.

- Woodrum, Eric and Bell, Arnold. “Race, Politics, and Religion in Civil Religion Among Blacks.” Sociological Analysis 49 (1989): 353-367

- Woolley, Donald Patrick. Perceptions of the Presidency. Civil Religion and the Public’s Assessment of Candidates and Incumbents. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag, 2008.

- Wuthnow, Robert . “Divided We Fall: America’s Two Civil Religions.” The Christian Century 115 (1988): 395-399.

- Yamane, David. “Introduction. Habits of the Heart at 20.” Sociology of Religion 68 (2007): 179-189.