"Obama and Language: Language Policy Areas and Goals in Presidential Communication" by Sándor Czeglédi

Sándor Czeglédi, Associate Professor at the English and American Studies Institute of the University of Pannonia in Veszprém, Hungary, holds a Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics/Language Policy from the University of Pécs. His publications include Language Policy, Language Politics, and Language Ideology in the United States (2008), as well as several articles on the “English-only” movement, bilingual education, and the realization of minority language rights in the United States. Email: czegledi@almos.uni-pannon.hu

1. Introduction

Setting language policies has rarely been a top government priority in the United States. Apocryphal accounts aside, the official language issue had not reached the Congressional floor until 1996 when Bill Clinton’s veto threat blocked the introduction of the “English Language Empowerment Act” in the Senate after the measure had received sizeable support in the House (Crawford 2000, 49).

Nevertheless, Clinton has left behind an enduring and contested language policy legacy in the form of Executive Order (EO) 13166, which was devised to end possible national origin discrimination by requiring federal agencies to ensure “meaningful” limited English proficient (LEP) access to their services in order to comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The presidential reinterpretation of “national origin” discrimination by executive fiat was immediately regarded by many as an unlawful extension of power. Consequently, some Republicans have repeatedly tried—as yet unsuccessfully—to pass legislation to revoke the order.

By and large, the Clinton administration’s language policy (LP) record was reflective of the multiculturalist view, understood as “not just … tolerance of cultural diversity in de facto multicultural societies but as the demand for legal recognition of the rights of ethnic, racial, religious, or cultural groups” (Fukuyama 2006, 9). The “language-as-right”-oriented attitude (Ruíz 1984) of Fukuyama’s definition was even surpassed by the 1994 Bilingual Education Act (“Title VII” or BEA), which sought to develop the “English of [LEP] children and youth, and, to the extent possible, the native language skills of such children” (BEA 1994, Sec. 7102 ©(2–3)).

This promotion-oriented educational policy was abruptly changed in January 2002 when George W. Bush signed into law the bipartisan “No Child Left Behind” Act (NCLB), which has placed heavy emphasis on English language learning in the name of “accountability,” (local) “flexibility,” and “choice, forcing schools to mainstream LEP students as soon as possible (Wright 2005, 20–26). No major reevaluation of Bush’s policies is to be expected any time soon by the current administration (Strauss 2010).

In addition to (minority) language status issues, several instances of corpus planning policies also reached the White House in the past century. One—unsuccessful—effort of this type was Theodore Roosevelt’s heavy-handed directive to reform English spelling in 1906 (Czeglédi 2008a, 384–85). That initiative was met with stiff Congressional resistance, unlike the recent Plain Writing Act of 2010 (H.R. 946), which passed the House by an overwhelming majority of the votes and received unanimous consent in the Senate.

H.R. 946 sets out to promote “clear Government communication that the public can understand and use” (H.R. 946, Sec. 2). The act, which might be regarded as a culmination of an at least 40-year-long Plain English struggle, defines plain writing as “clear, concise, well-organized,” and one that follows “best practices appropriate to the subject or field and intended audience” (H.R. 946, Sec. 3(3)).

Presidents—with the exception of Ronald Reagan—have largely supported the incorporation of Plain English requirements into official government documents since the 1970s (Locke 2004). Although this topic was not discussed during the presidential campaign in 2008 (Czeglédi 2010: 215–29), the present analysis will show its central importance to Barack Obama’s LP agenda.

2. The Corpus and the Method of Analysis

In order to map the most salient language policy issues that appeared explicitly on the presidential agenda during Obama’s first year in office (from January 20, 2009 to January 20, 2010), I used the searchable “Public Papers” archive of “The American Presidency Project” (http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/), maintained by John Woolley and Gerhard Peters. The search string was “language” AND/OR “languages,” which returned 133 different hits for the specified period (including documents from the Office of the Press Secretary). After removing the irrelevant documents (e.g. the ones that contained references to the “legislative language” of a bill or to the “strong language” of a statement) there remained 41 instances that were pigeonholed as either symbolic or substantive LP statements. As a rule of thumb, the latter category contains those documents that directly address tangible issues or problems (and usually allocate resources) in order to change the status quo. Borderline cases and overlaps sometimes occur, however.

For the categorization of policy statements, Moshe Nahir’s eleven-point classification of “language planning goals” (Nahir [1984] 2003) presented itself as a likely descriptive framework. The matrix had originally been laid down to cover the totality of language planning functions, with the purpose of trying to establish what various agencies “have been or may be seeking” in this area (Nahir [1984] 2003, 425, italics in the original).

Based on the findings of previous research into the LP-related activities of the US Federal Congress (Czeglédi 2008b), the original list was extended to seventeen points, to which further two were added in order to give a more thorough account of the presidential perspective on language-related issues. (Throughout this paper the terms “language policy” and “language planning” are used interchangeably.)

Nancy Hornberger interprets “Revival” (2), “Spread(ing)” (5), “Interlingual Communication” (9), and “Maintenance” (10) as exemplifying “status cultivation”; while “Purification” (1), “Reform” (3), “Lexical Modernization” (6), “Terminology Unification” (7), and “Stylistic Simplification” (8) belong to “corpus cultivation.” The notion of “Standardization” (4) embraces both status and corpus aspects, including “Auxiliary-Code Standardization” (11) as its subordinate term illustrating corpus cultivation (Hornberger 2003, 453–54).

Table 1: Nahir’s extended descriptive framework of language planning goals

(including Nancy Hornberger’s corpus planning and status planning goals) Italics indicate categories not mentioned in Nahir’s original systematization.

|

Protecting the language from external (foreign) influence and/or internal (substandard) deviation. |

|

Attempting to turn a language with few or no surviving native speakers into a normal means of communication in a community. |

|

Deliberately changing specific aspects of the language (e.g. orthography, spelling, lexicon, or grammar) in order to facilitate its use. |

(having both status and corpus planning aspects) |

Having a language or a dialect accepted as the major language of the region which is usually a single political unit. |

|

Attempting to increase the number of speakers of a language at the expense of another language.1 The hastening of language shift,2 often motivated by political considerations. |

|

Word creation/adaptation as a way to assist developed, standard languages that have borrowed concepts too fast to accommodate. |

|

Establishing unified terminologies (mostly technical). |

|

Simplifying language usage in lexicon, grammar, and style in order to reduce communicative ambiguity (e.g. fighting “legalese,” “bureaucratese”). |

|

Facilitating linguistic communication between members of different speech communities by enhancing the use of either an artificial (or “auxiliary”) language or a “language of wider communication”3 used as a lingua franca. |

|

Preserving the use of a group’s native language4 as a 1st or even as a 2nd language in the face of political, social, economic, educational, or other pressures. |

|

Standardizing the auxiliary aspects of language, e.g. signs for the deaf, place names, rules of transliteration and transcription. |

|

Granting a given language official status. |

|

Banning or restricting the use of a given language. |

|

Granting political, legal, educational, health care, etc. access to (government) services. |

|

Supporting pre-K-12 and adult English literacy programs. |

|

Promoting foreign (and/or minority) languages in order to strengthen national security. |

|

Employing cultural diplomacy to spread the English language and American ideals abroad. |

|

Accepting and/or promoting multilingualism and multiculturalism as an asset (L-as-Resource orientation). |

|

Accepting and/or promoting multilingualism and multiculturalism as an asset (L-as-Resource orientation). |

Based on Nahir’s “Language Planning Goals” ([1984] 2003).

3. Findings

3.1 General Overview

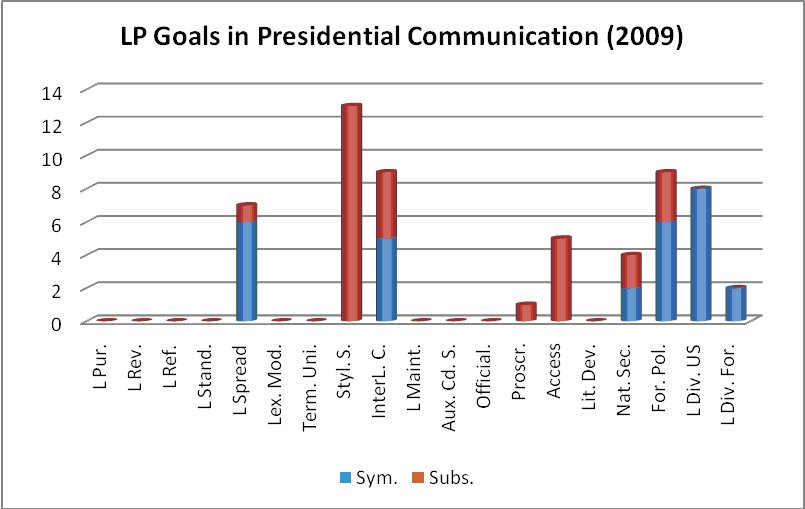

Out of the nineteen LP goals outlined in the extended version of Nahir’s descriptive framework above, nine categories were eventually represented in the 41 relevant documents dated between January 2009 and January 2010. The distribution of symbolic vs. substantive pieces was roughly even, 28 to 29. Several documents contained references to more than one LP goals, some of which were regarded as symbolic, others as substantive.

The entirely symbolic categories were the ones that praised the virtues of linguistic and cultural diversity either in the United States or abroad (18; 19). Coupled with the fact that minority language maintenance (10) received zero attention, this attitude suggests an overwhelmingly assimilationist stance beneath the veneer of pluralist rhetoric.

Conversely, the clearly substantive nature of Stylistic Simplification (8) and Access (14) indicates an entirely different level of executive commitment to the achievement of these LP goals.

In view of previous observations made on the history and nature of U.S. language policy and language ideology (Czeglédi 2008a, 2008b), the finding that very few corpus planning-related policies were found in presidential communication is hardly surprising. In fact, only Stylistic Simplification appeared, yet it turned out to be the most unequivocally endorsed policy by Barack Obama during the examined period.

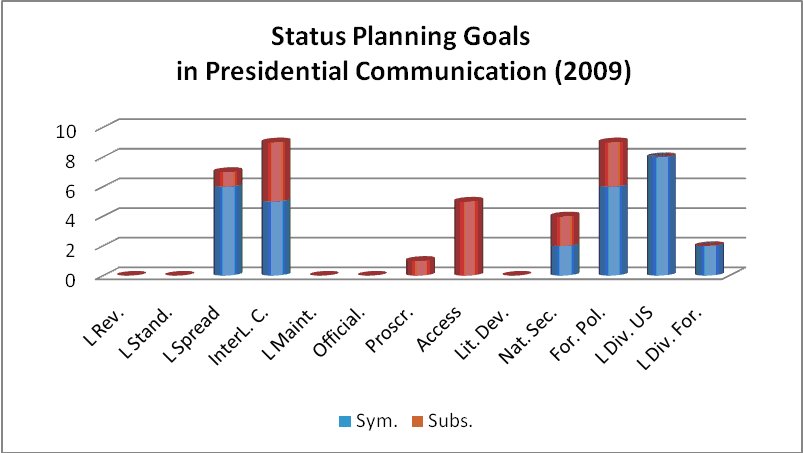

Status planning references, on the other hand, cropped up in the form of Language Spread, Interlingual Communication, Proscription, Access, National Security, Foreign Policy and Language Diversity (both in the U.S. and abroad).

The most frequently endorsed themes within the LP context were Interlingual Communication and the closely related category of Language as a Foreign Policy Instrument. Providing Access to (government) services proved to be the most substantive LP goal among the status planning policies.

3.2 Language Planning Goals in Detail

3.2.1 Corpus Planning

References to Stylistic Simplification occurred thirteen times in the examined documents. The overwhelming majority of these policy proposals emerged in the context of financial regulation, and eventually these proposals were incorporated into H.R. 627, the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009. The promotion of “openness,” “transparency, and “plain language” throughout the financial system was the top language policy priority of the Obama administration during 2009, as a result of which all forms and statements by credit card companies are now required to be written in plain language: no more “fine print” or confusing terms are allowed that might prevent people from making informed choices (“Remarks Following a Meeting With Economic Advisers”).

In order to protect consumer rights, the Obama administration also proposed the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Agency, which is also entrusted with the enforcement of plain language requirements in the financial system (ibid.)

The plain language policy was given presidential support in the field of health care as well: the administration’s planned health insurance exchange is to function as a “one-stop shop for health care plans [where people can] compare benefits and prices in simple, easy-to-understand language” (“Remarks at a Virtual Town Hall…”).

Finally, Stylistic Simplification appeared (somewhat tangentially) in the educational context, too: Secretary of Education Arne Duncan outlined the simplified procedure of FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid) application, which was redesigned to serve the needs of families for whom “English [is] the second language” (“Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, IRS Commissioner Doug Shulman, and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan”).

3.2.2 Status Planning

Language Spread(ing)

Out of the seven instances found in this category, only one appeared to be substantive. In his remarks at James C. Wright Middle School in Madison, Wisconsin, the President praised the Race to the Top grants and emphasized the general need to increase “the numbers of quality teachers who can help our special education and English language learners meet high standards” (“Remarks to Students, Faculty, and Parents…”). Since these policies basically emphasize the accelerated learning of the majority language to the detriment of bilingual education methods, labeling the statement as substantively Language Spread-oriented seems justifiable.

The other Language Spread cases included Obama’s April 7 discussion with students in Istanbul where the President held out Robert College, the nearly 150-year-old American high school in Turkey as an exemplary institution (“Remarks in a Discussion With Students…”); references to his trip to Georgia and the planned visit of an USAID summer camp focused on developing mathematics and English skills (“Press Briefing by National Security Advisor to the Vice President…”); and anecdotes told by South Korean leaders about the huge demand for English teachers in their country (“Remarks at Lehigh Carbon Community College…”).

Interlingual Communication

In the area of Interlingual Communication there is a considerable overlap with the symbolic Language Spread category (i.e. with the previously mentioned Turkish, Georgian and South Korean examples).

In addition, the President emphasized and substantively endorsed the development of the foreign language skills of military personnel to help them “succeed in the unconventional mission that they now face” (“Remarks at the National Defense University…”). This commitment was repeated at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona (“Address at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention…”).

Moreover, Barack Obama denounced the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy as adversely affecting national security interests because it might lead to the discharge of “patriots who often possess critical language skills” (“Remarks at a Reception Honoring Lesbian…”). Yet no specific policies to end the practice were outlined in the speech.

Furthermore, the President had his April 2009 message to Cuba broadcast in Spanish, in which—after 50 years of enmity—Barack Obama announced to ease travel and remittance restrictions still in force against the Communist country (“Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs and Dan Restrepo…”).

In a similar fashion, the Interlingual Communication and Language as a Foreign Policy Instrument goals became intertwined in Obama’s speech at Cairo University on June 4, focusing on the possibility of a new beginning between the U.S. and the Muslim world: the address was translated into 13 different languages (“Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, Speechwriter Ben Rhodes…”).

Proscription

The only case belonging here was a reference to the ignominious practice of eradicating Native American languages and cultures in the past, for which the President apologized to tribal leaders at the opening of the American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations Conference. (“Remarks at the Opening of the American Indian…”).

Access

All relevant instances were substantive among the Access-type policies. References were made to the Spanish-language website of the Center for Disease Control that contains information on swine flu; to various ways of helping unprepared households in the transition to digital television (i.e. by airing advertisements in Spanish and handing out coupons to the needy); and to the creation of the health insurance exchange (see Stylistic Simplification in 3.2.1).

The most significant Access-oriented (language) policy initiative by the President in 2009 was the signing of Executive Order 13515. It is aimed at increasing the participation of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (who might be in a disadvantaged position, for example due to the existence of the “language barrier) in federal programs (“Remarks on Signing an Executive Order…”). A specifically mentioned language-related policy for AAPIs was the need for continued “language assistance and equal access to the polls” (ibid.).

EO 13515 superseded Bill Clinton’s similar measure (EO 13125)—which was signed in June 1999—and was renewed, amended and extended by George W. Bush’s EO 13216 two years later and by EO 13339 in 2004. Despite its relatively long history, no references to language problems had been made in the AAPI access policy before 2009.

No specific language policy initiatives are outlined in the current EO 13515 either: it establishes (in the Department of Education) the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with the mission to provide advice to the President through the Secretaries of Education and Commerce “on the development, monitoring and coordination of executive branch efforts to improve the quality of life of AAPIs through increased participation in Federal programs in which such persons may be underserved” (EO 13515 Sec. 2(a)(i)).

National Security

The symbolic pieces in this category were the remarks criticizing the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in the military since this might lead to the loss of invaluable foreign language skills as well (see Interlingual Communication), and the proclamation of Native American Heritage Month, in which Barack Obama reminded the nation that Native American code talkers played a pivotal role in both World Wars (“Proclamation 8449”).

The substantive policy initiatives were the remarks at the National Defense University and the address at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention (see Interlingual Communication).

Language as a Foreign Policy Instrument

Among the symbolic presidential declarations there appeared one example where the English language served as the unquestionable bridge that helped to cement a unique, historical friendship with an overseas country: the “special relationship” with Great Britain (“Remarks Following a Meeting With Prime Minister Gordon Brown”). Implicitly, this common cultural trait contributed to the amiable and collegiate atmosphere at the meeting with the Prime Minister of Ireland as well (“Remarks at a Saint Patrick’s Day Shamrock Presentation Ceremony…”).

The other symbolic Foreign Policy Instrument cases were focused on the planned telecasting of presidential speeches in a variety of languages and on visiting the USAID camp in Georgia (see Language Spread).

The substantive cases included the remarks at the National Defense University (see Interlingual Communication); the endorsement of student exchange programs in general and the mission of Robert College in particular (see Language Spread); and the President’s message to Cuba broadcast in Spanish as well (see Interlingual Communication).

Language Diversity and National Identity

This category comprises wholly symbolic statements, which means that no policies were actually made or announced to promote linguistic diversity—the presidential attitude is probably best summed up by the labels of “expediency”—the provision of short-term minority-language accommodation—and “tolerance”—a predominantly laissez faire-type of behavior—according to Terrence G. Wiley’s framework for LP analysis (1999, 21–22).

The very first endorsement of language diversity in general can be found in Barack Obama’s Inaugural Address: “For we know that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness… We are shaped by every language and culture, drawn from every end of this Earth” (“Inaugural Address”).

The next occasion was the President’s visit to Mexico: “All across America, all across the United States, we have benefited from the culture, the language, the food, the insights, the literature, the energy, the ambitions of people who have migrated from our southern neighbor” (“Remarks at a Welcoming Ceremony…”).

The other symbolic instances were the proclamation of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (“Proclamation 8369”), Native American Heritage Month (“Proclamation 8449”), and that of National Angel Island Day (“Proclamation 8475”); remarks at the Cinco de Mayo celebration (praising the enriching effects of Hispanic culture—including the Spanish language) (“Remarks at a Cinco de Mayo Celebration”); remarks to the International Olympic Committee in Copenhagen (in support of Chicago’s 2016 bid by stressing the city’s multiethnic and multilingual nature) (“Remarks to the International Olympic Committee…”); and the opening address at the American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations Conference (“Remarks at the Opening of the American Indian…”).

Linguistic Diversity and Non-American Identity

Barack Obama praised linguistic and cultural diversity abroad in two speeches. The first occasion was in Strasbourg (in a historical reference to the Oaths of Strasbourg). It was there, during the question and answer session, that a girl from Heidelberg told Barack Obama the Hungarian meaning of his first name—giving rise to the “peach v. apricot” dilemma in Hungarian Anglophone circles (Purger 2009).

The second occasion took place in Accra, Ghana, where the President spoke highly of the successes of this multiethnic and multicultural African democracy (“Remarks prior to the departure…”).

4. Conclusion

Out of the nineteen examined LP categories nine were represented in the presidential communication during the first year of the Obama administration. The ones that were conspicuously missing—although they have a considerable following among members of Congress and/or can be identified as components of extant policies—are Officialization and Literacy Development in the Majority Language. The former issue was constantly avoided and dismissed by Senator Obama during the 2008 campaign as “divisive” (Czeglédi 2010, 222–24), yet the growing number of cosponsors behind H.R. 997, the flagship Official English bill of the 111th Congress indicates that the President will soon have to take sides in the question (although he had voted against a “national language” declaration in the Senate back in 2007). The political consensus behind Literacy Development in English appears to be unbroken as long as the bipartisan support behind NCLB remains intact.

Throughout 2009, the achievement of Stylistic Simplification (Plain English) goals in the context of reforming the financial system dominated the LP-related presidential statements. Although the tendency could be interpreted as yet another manifestation of “Big Government” activities, from the pluralist perspective the fact that “openness” and “transparency” are to be realized through exclusive reliance on the majority language sends an unambiguously assimilation-oriented message. This type of monolingualization of equity considerations meshes with the rapid spread of sheltered/structured immersion as a “bilingual” education method in schools, with the state-level tendencies of adopting English as the official language—and with the mounting support behind Official English bills in the federal Congress.

Among the status planning goals, the Language Spread examples illustrated the importance attached to the school system in Americanizing the young immigrant generations. Minority languages were not mentioned in the educational context, which suggests a “language-as-problem”-type of presidential attitude in K-12 settings. Efforts to aid the global spread of English were also present among the LP priorities—at least at the level of high profile visits to institutions involved in this missionary work.

Substantive Interlingual Communication goals correlated with National Security and Foreign Policy priorities. Improving foreign language proficiency in the military was a top priority in 2009, and the President also promised to change current regulations that might unfairly discriminate against the homosexual members of the armed forces. Thus, with a master stroke, Barack Obama cast homophobia as an unpatriotic form of behavior as this attitude could effectively weaken the nation’s preparedness level in terms of critical foreign language skills.

Access to government services was to be strengthened specifically in the fields of health care and the media (i.e. with respect to transition to digital television). Nevertheless, the more far-reaching policies—the creation of the health insurance exchange—did not entail the legitimation of heritage languages in the process, since it is Plain English requirements that are to be employed in order to facilitate minority access to the best health care options available.

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders were given special attention by the Chief Executive through EO 13515, yet even this seemingly generous policy treats linguistic diversity mostly as a problem: according to the official opinion, AAPI participation in federal programs might be hindered by the existence of the “language barrier.” No references were made to AAPI languages in a “language-as-resource” context.

Overall, during the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency, minority languages were largely cast in the “language-as-problem” mold in the substantive LP-related official statements—whereas the President was significantly more willing to describe linguistic diversity as an asset in his wholly symbolic speeches and remarks. Although “foreign” language skills were clearly appreciated in the National Security context, no attempt was made to remedy the shortage of linguistically proficient personnel by relying on the not-yet-fully-assimilated immigrant generations, which stance reinforces earlier sociolinguistic observations made e.g. by Rolf Kjolseth (qtd. in Crawford 2004, 65) on the “schizophrenic” nature of American language ideology. The tendency that simple, plain English is increasingly offered to minorities instead of the recognition of heritage language use in specific domains also signals the return to the “melting pot”-type interpretation of linguistic diversity in the United States.

Works Cited

- “Address at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86545.

- Bilingual Education Act (BEA) of 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-382. Accessed February 11, 2002. http://www.ncbe.gwu.edu/miscpubs/gov/titlevii/tvii.htm.

- Crawford, James. 2000. At War with Diversity: US Language Policy in an Age of Anxiety. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- ———. 2004. Educating English Learners: Language Diversity in the Classroom. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Bilingual Education Services.

- Czeglédi, Sándor. 2008a. “A nyelvművelés helyzete az Egyesült Államokban.” In Európai nyelvművelés: Az európai nyelvi kultúra múltja, jelene és jövője, edited by Géza Balázs and Éva Dede, 379—96. Budapest: Inter Kht.-Prae.hu.

- ———. 2008b. Language Policy, Language Politics, and Language Ideology in the United States. Veszprém: Pannonian University Press.

- ———. 2010. “Problem, Right or Rhetoric? Language Policy Issues on the Presidential Candidates’ Agenda.” In CrosSections. Vol.1, Selected Papers in Linguistics from the 9th HUSSE Conference, edited by Irén Hegedűs and Sándor Martsa, 215—29. Pécs: Institute of English Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Pécs.

- Exec. Order No. 13515, “Increasing Participation of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Federal Programs.” Accessed September 12, 2010. http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2009/pdf/E9-25268.pdf.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2006. “Identity, Immigration, and Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 17 (2): 5—20.

- Hornberger, Nancy. 2003. “Indigenous Language Revitalization, Biliteracy, and Student Voice: Instances from Quechua, Guarani, and Maori Bilingual Education.” Plenary talk presented at the Dialogue on Language Diversity, Sustainability and Peace, Linguapax Institute, Barcelona, May 21. Accessed April 23, 2005. http://www.linguapax.org/congres04/pdf/hornberger.pdf.

- “Inaugural Address.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=44.

- Locke, Joanna. 2004. “A History of Plain Language in the United States Government.” Accessed July 27, 2006. http://www.plainlanguage.gov/whatisPL/history/locke.cfm.

- Nahir, Moshe. (1984) 2003. “Language Planning Goals: A Classification.” In Sociolinguistics: The Essential Readings, edited by Christina B. Paulston and G. Richard Tucker, 443–48. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Plain Writing Act of 2010, H.R. 946. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h111-946.

- “Press Briefing by National Security Advisor to the Vice President Tony Blinken on the Vice President’s Upcoming Trip to Ukraine and Georgia.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86436.

- “Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs and Dan Restrepo, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Western Hemisphere Affairs.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85997.

- “Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, IRS Commissioner Doug Shulman, and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86325.

- “Press Briefing by Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, Speechwriter Ben Rhodes, and Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications Denis McDonough.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86240.

- “Proclamation No. 8369—Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, 2009.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86098.

- “Proclamation No. 8449, “National Native American Heritage Month, 2009.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86829.

- “Proclamation No. 8475—National Angel Island Day, 2010.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=87430.

- Purger, Tibor. 2009. “Tudja már Barack, mit jelent a barack.” Magyar Szó.com, April 4. Accessed September 28, 2010. http://www.magyarszo.com/fex.page:2009-04-04_Tudja_mar_Barack_mit_jelent_a_barack.xhtml.

- “Remarks at a Cinco de Mayo Celebration.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86103.

- “Remarks at a Reception Honoring Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86359.

- “Remarks at a Saint Patrick’s Day Shamrock Presentation Ceremony With Prime Minister Brian Cowen of Ireland.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85871.

- “Remarks at a Virtual Town Hall and a Question-and-Answer Session on Health Care Reform in Annandale, Virginia.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86368.

- “Remarks at a Welcoming Ceremony in Mexico City, Mexico.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86018.

- “Remarks at Lehigh Carbon Community College and a Question-and-Answer Session in Allentown, Pennsylvania.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86971.

- “Remarks at the National Defense University.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85854.

- “Remarks at the Opening of the American Indian and Alaska Native Tribal Nations Conference and a Discussion With Tribal Leaders.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86854.

- “Remarks Prior to the Departure from Accra, Ghana.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86393.

- “Remarks to the International Olympic Committee in Copenhagen, Denmark.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86854.

- “Remarks Following a Meeting With Economic Advisers.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85793.

- “Remarks Following a Meeting With Prime Minister Gordon Brown of the United Kingdom and an Exchange With Reporters.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85814.

- “Remarks in a Discussion With Students in Istanbul, Turkey.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=85971.

- “Remarks on Signing an Executive Order Increasing Participation of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Federal Programs.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86768.

- “Remarks to Students, Faculty, and Parents at James C. Wright Middle School in Madison, Wisconsin.” In The American Presidency Project, edited by John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 10, 2010. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=86856.

- Ruíz, Richard. 1984. “Orientations in Language Planning.” NABE Journal 8: 15–34.

- Strauss, Valerie. 2010. “Obama and NCLB: The Good—and Very Bad—News.” The Washington Post, March 13. Accessed September 2, 2010. http://voices.washingtonpost.com/answer-sheet/education-secretary-duncan/obama-and-nclb-the-good—and-v.html.

- Wiley, Terrence G. 1999. “Comparative Historical Analysis of U.S. Language Policy and Language Planning: Extending the Foundations.” In Sociopolitical Perspectives on Language Policy and Planning in the USA, edited by Thom Huebner and K. A. Davis, 17–37. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Woolley, John T., and Gerhard Peters. 2010. “The American Presidency Project.” Santa Barbara, CA. Accessed September 9. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/.

- Wright, Wayne E. 2005. Evolution of Federal Policy and Implications of No Child Left Behind for Language Minority Students. Tempe, AZ: Language Policy Research Unit, Education Policy Studies Laboratory, Arizona State University. Accessed March 28, 2005. http://www.asu.edu/educ/epsl/EPRU/documents/EPSL-0501-101-LPRU.pdf.

Notes

1 In the present classification, this category includes conscious attempts to aid the global spread of English as well, but such cases are also included in the “Language as a Foreign Policy Instrument” (17) group. ↩

2 Consequently, all policies that promote the “weak” (transitional) forms of bilingual education (BE) belong here. ↩

3 If “the language of wider communication” is English, then the proposal is also listed in the “Language Spread(ing)” (5) and/or “Language as a Foreign Policy Instrument” (17) categories. ↩

4 In the original article, Nahir distinguished between dominant language maintenance and ethnic language maintenance. In this classification, “Maintenance” (10) refers to the preservation of the minority language. ↩