"Otherness Incorporated: Halsey as the Contemporary Media Rebel" by Petra Visnyei

Petra Visnyei is an MA student at the Department of British Studies, Institute of English and American Studies, University of Debrecen. Her research interests include gender, rape culture, transgressive gendered identities and their representation in contemporary culture, literature, film adaptations and comics. Email: petravisnyei@gmail.com

INTRODUCTION

This study is an attempt to investigate the character of Halsey, an edgy, diverse artistic persona created by pop-powerhouse Ashley Nicolette Frangipane, a 21-year-old singer and musician performing in the electro-pop and alternative-pop genres, who started out as a youtube and tumblr celebrity, building up and strengthening her fan base via these media. The primary purpose of this paper is to explore how a young adult attempts to break the mold and have an impact on the general tendencies of the misogynist, male-favoring music industry – going against social pressures and sexism, having to deal with criticism from various sources. The thesis will attempt to give a detailed insight into the circumstances surrounding the artistry of a young, biracial, bipolar and bisexual woman – exploring the social and cultural phenomena that encompass performers in an undeniably male-dominated mainstream culture and examining the antecedents that fuelled the various stereotypes and preconceptions that still contribute to the ways female artists are perceived today. One aim of this paper is to describe the position of female performers in the market-oriented music industry, exploring the reason why they are at a disadvantage compared to male counterparts, thus outlining the inequity of the two sexes. Halsey will be taken as a representative of the contemporary female rebel, as she engages in the construction of still fragile and assailable identities and concepts; that of the young female, the bipolar, the mixed-race and the bisexual who do not fit in with the ideologies and preconceived notions of heteronormativity. Finally, through investigation of her artistic endeavor and personal attitude to the industry, by analysis of interviews, interpretation of her lyrics and her visual representation, the thesis will examine how she tries to challenge the still-lingering patriarchal oppression.

"I don’t like them innocent

I don’t want no face fresh

Want them wearing leather

Begging, let me be your taste test"

(Halsey. – "Ghost")

1. WOMEN’S PLACE IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY

1.1 The Formation of Gendered Attitudes – Social Construction and Media Gimmicks

Culture is generally and fundamentally gendered, thus enforcing a gendered media, which shapes the representation of men and women as well as in popular culture as in different subcultures – as Adrienne Trier-Bienek and Patricia Leavy’s recent introduction to Gender & Pop Culture also asserts: "Since gender is socially constructed and not innate, we learn gender norms through interactions with people and cultural texts and objects" (17). To explain this: gender is not congenital, but a framed presumption which society creates by exposing the masses to preconceptions, thus influencing the very concept of gender. Along similar lines, Angharad N. Valdivia’s essay on feminism and media studies claims that:

Because the study of mass communications is central to the contemporary condition, it is not surprising that media studies research yields provocative answers or paths to the understanding and discussion of multicultural feminist issues. In fact, [ . . . ] The Feminine Mystique (1963), privileged the mass media as an indicator and site of struggle over gender politics. [ . . . ] feminists have learned much about the pervasiveness of sexist patterns, the difficulty of changing these patterns, and the media’s role in the establishment, continuity, and breaking these patterns. (8-9)

Valdivia argues that, in order to understand the contemporary multicultural sphere, the discussion of problems and questions that go beyond mainstream white feminism, is essential, and to interpret these issues, one must look into the depths of mass media.

Gender, class, ethnicity, sexual orientation and financial background each affect how the media treats an artist. Leavy and Trier-Bienek explain that social constructions create a duality between the sexes: "[ . . . ] gender, (our ideas about masculinity and femininity), becomes stereotyped and overgeneralized. In our culture, social constructions create a gender binary where masculinity and femininity are seen as polar opposites" (17). The main object of gendered media is to fabricate patterns and systems in order to legitimize the sexual and societal rules that set boundaries and disparity between men and women; to conciliate a gendered media with society. Countless essays and articles deal with this issue, as it has become a general phenomenon. As Cynthia Carter discusses in a comprehensive examination of sex roles and social construction in "Sex/Gender and the Media: From Sex Roles to social construction and Beyond", some of the earliest media research looked at sex and gender distinctions as portrayed by the press, television, films and magazines (370). My investigation of various TV programs, commercials, magazines, interviews, articles and music videos led to the same conclusion. I inspected that female performers of numerous genres and cultural layers face an unjust differentiation in their profession, as opposed to males who are inevitably advantaged – even as the whole of the mass media has become a field of objectification, the heterosexual male artist still remains superior in his objectified state, standing as an idealization, being either an exalted, unrestricted, yet desirable manifestation of masculine sexuality, or, if desexualized, as a sublime, exemplary form of self-mastery and grandeur. The female artist, in contrast, is treated as inferior; if seen as openly sexual, she is viewed as a delinquent, feverish, uncontrollable and dangerous presence of lush fervor, or, if she is not sexual in her performances and artistry, she can most easily be accused of prudishness and restriction, of being offbeat and lacking sex appeal, someone who is unusual in her frigidity. Furthermore, the more complex and peculiar her sexuality and appearance is, whether she is a homosexual or bisexual artist, or an androgynous individual, the more intensely the mass audience and her competitors will criticize her. Leavy and Trier-Bieniek’s research also confirms my claims: "Some feelings, behaviors, preferences, and skills are attributed to females and others to males. When people cross those lines they can be subject to ridicule or worse" (17). Not meeting the gendered rules and regulations that are pre-set for her, thus displaying traits that the mainstream heteronormativity is not accustomed to and cannot accept, the uncustomary female artist continues to fuel the stubborn anger and blind partiality of the masses. Valdivia examines that questions and issues of diversity, multiculturalism and feminism "interfere with a preset order" and are "neither mutually exclusive nor equivalent and interchangeable." She differentiates two reactions to these issues, naming ‘denial’ as the first way (12). The music industry also differentiates performers based on racial features and global origin, overlapping the issues of class and gender. Each of these factors contribute to the oppression of women in the industry and the underrepresentation of matters surrounding the handling of gender, race, sexuality and class, as it is described by the second approach:

[ . . . ] a second "natural" option is to fit these issues into binary oppositions. Thus we have issues set in "black or white" frameworks. We have rich or poor, male or female, masculine or feminine, gay or straight, rational or irrational, local or global, nature or culture, multicultural or monocultural. In this progress, the issues of diversity are fitted into a preexisting framework of analysis foregrounded by binary oppositions. (12)

1.2 The Bold Wunderkind – Overturning Characterization

In the midst of these preset oppositions, Ashley Frangipane created Halsey as "not quite an alter-ego as much as it’s just an amplified version of [ herself ]" as she claimed in an interview with Peter Robinson. Halsey stands as a most intricate amalgam; she is possibly one of the most unique artists on the scene, because, paradoxically, she fits into so many categories of "not-fitting in" – by being a young, biracial, bisexual female with feminist views and peculiar approaches to everything from self-promotion to artistic expression, that she practically creates a new category which is, as yet, undefined. Joe Coscarelli describes Halsey in a music review for The New York Times, as a kid from New Jersey with 14,000 friends on MySpace at age 14 and 16,000 subscribers on YouTube at 18. She is the millennial provocateur, yet, she does not consider herself the voice of a generation – she claims that she only speaks for herself (Robinson). It was her debut EP, "Ghost", which kick-started her carrier, in her own words: "[ . . . ] I wasn’t in bands, I didn’t have any representation, and I had no interest in being a singer. [ . . . ] After I put "Ghost" up online, that night I was heard by five record companies. [ . . . ] From that day on I’ve been an artist" (Weatherby).

Halsey’s general approach to self-expression is daring and unapologetic: "If I’m not offending anyone’s race or creed or beliefs to a level of political incorrectness, then why do I have to fucking please anyone? I have no-one to please" (Graves). She is an openly proud bisexual woman and a dedicated feminist – her mixed race and her mental illness make her incredibly important in the industry, because of her intersectionality regarding POC issues, LGBT issues, feminist issues and white-washing. Her race is a much complex question, as she can be considered "white passing," meaning that even though she is technically biracial, she could easily "pass" as a white person, which often led to criticism and accusations of tokenizing herself, to be further elaborated on in Chapter Two. She is a relative new-comer, yet with a voice artistically unique, and with a still-developing fan-base rapidly growing in size which considers her as a massive inspiration and role model for different sexualities and ethnicities.

In Spectacular Girls: Media Fascination and Celebrity Culture, Sarah Projansky presents a typology of girls in contemporary media, differentiating two opposing types and, paradoxically, Halsey complies with both. The first type is the can-do girl, who is described as confident, resilient, smart, empowered, a successful athlete, independent, beautiful and fit, a girl who has the world right at her feet (2-4).

This version of girlhood is a fantasy promise that if girls work hard, not only can they avoid becoming at-risk, but they can achieve anything. […] this narrative promises unbelievable happiness and achievement—girl power—for the girl who embodies can-do status through career, fashion, and lifestyle choices. (5)

Simon Reynolds also mentions the concept and origins of the can do girl in his essay titled "Double Allegiances: The Herstory of Rock." The "can do approach, as in ‘anything a man can do, a woman can do too’ [ . . . ] runs from Suzi Quatro through Joan Jett to L7: hard rock, punky attitude, women impersonating toughness, independence and irreverence of the male rebel posture" (231). The second type is the at-risk girl who lacks self-esteem and/or engages in risky behavior, who is depressed, can be a pregnant teen, is hyper-sexualized at too young an age, engages in drug usage and unprotected sex, and loses her voice. (Projansky 2-4). As Halsey explains in a Billboard interview: "I’m 20, but I feel 40, [ . . . ] Kids I grew up with are going off to college, having threesomes in bathrooms and ‘vaping’ beer, but I went through my sex, drugs, loss and existential confusion phase at 17" (Martins). As Projansky explains, the media generates an eagerness in girls to resemble an unattainably sexual depiction of girlhood, which results in their early sexual engagement: “Media depictions of hyper-sexualized girls lead to decreased self-esteem and potentially poor choices to put one’s own body on display or engage in early sexual activity" (5). Media not only stresses hyper-sexualization, but enforces judgmental connotations regarding hyper-sexualized girls, resulting in ethical anxiety:

Yet, in the process of “reporting” on and worrying about this, media further perpetuate the at-risk narrative, reproducing and reifying images of girls as hyper-sexualized and miserable. In short, media contribute to the creation of the at-risk narrative, produce a moral panic about the girl figure at the center of that narrative, and then—through the process of worrying—perpetuate the very depictions of girls about which they worry. (5)

Halsey embodies features and mixes patterns of both depictions, as she has every attribute to fit into the character of the can-do girl, but, her persona is tinged with qualities of the at-risk girl. She is most certainly a blend of the two types, as she stands as a successful, talented, ground-breaking individual, yet her dark, edgy lyrics are often centered around depression or heartbreak, with eerie, unusual musical notes and out of the ordinary music videos to accompany her self-expression. Her music is calculated chaos: varying between low and high dynamic ranges, one main melody is accompanied by various simultaneous melodies echoing in the background, taking soft, quiet fade-ins as pre-chorus and pairing them with an intense, explosive, piercing chorus to be followed by muted fade-outs, all the while switching back and forth between noisy, crowded, harsh sounds and muffled, lackluster, opaque ones. The lyrics are biting and emotional, and have a pattern of recurring motifs.

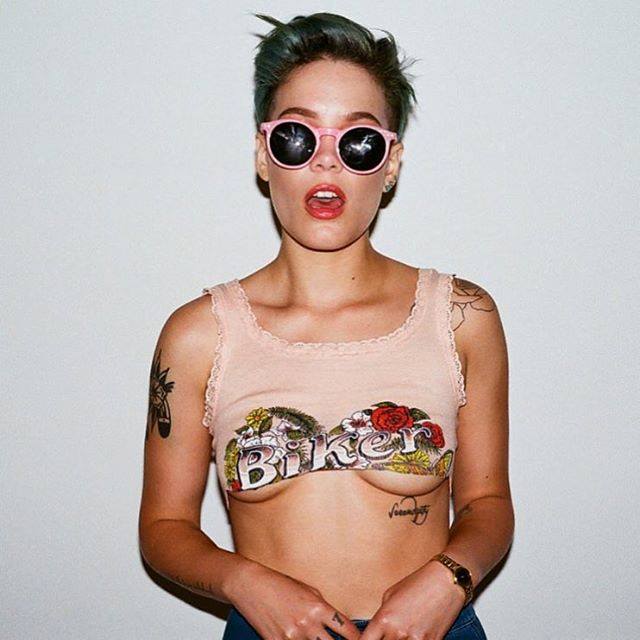

Reynold’s description of Patti Smith shows a notable parallel between Halsey and American singer-songwriter Patti Smith. As Reynolds explains, Smith was caught in a crossfire of the traditions of the patriarchy and of the male rebel. Even more strongly, in her times, a woman was limited to being the mistress or being the muse (236). Talking about photo shoots, Halsey herself also takes notice of this duality: "[ . . . ] it’s funny because it either goes one way or the other: They’ll either try to sweeten me up or they’ll play the bad girl thing so obnoxiously" (Harman). The two photos of Halsey below illustrate these tendencies: in the first one, she is seen with an innocent expression, wearing quite a classic necklace, her long hair delicately framing her face, long false lashes adding to a wide-eyed, childish expression. Not much of her skin is showing as her tee-shirt covers her up to her neck.

Figure 1. Halsey with long hair. Photo: Halsey (2015).

The second photograph shows Halsey with short, ruffled hair, a tiny, cut-up tank top that reads ‘Biker’, with the underside of her breasts and her tattoos very visible, sunglasses over her eyes and her mouth slightly open in a provocative manner. The image depicts her as a bad girl, tough but sexy.

Figure 2. Halsey with short hair. Photo: Halsey (2015).

The duality seen on the two pictures above is also present in Halsey’s lyric themes.

There’s a place way down in Bed-Stuy

Where a boy lives behind bricks

He’s got an eye for girls of eighteen

And he turns them out like tricks

I went down to a place in Bed-Stuy

A little liquor on my lips

I let him climb inside my body

And held him captive in my kiss"

(Halsey. – "Hurricane")

The lyrics of "Hurricane," for instance, describe how a young girl falls into early sexual usability, and how that wrecks her psychologically, yet, the lines hold a strong sense of empowerment. Halsey explains that "Hurricane" "actually has the strongest feministic [sic] element because it takes these words like ‘one-night stand’ that previously has this negative connotation for it being ‘slutty,’ but I turn it into a positive by saying that I don’t belong to anyone" (Kohn). The lyrics read as follows:

I’m a wanderess

I’m a one night stand

Don’t belong to no city

Don’t belong to no man

I’m the violence in the pouring rain

I’m a Hurricane

(Halsey. – "Hurricane")

The "hurricane" motif reemerges in another song titled "Gasoline:" "Do you call yourself a fucking hurricane like me?/ Pointing fingers cause you’ll never take the blame like me?" These haunting, dark images paired with echoing, peculiar music, add to the at-risk girl persona. However, it is particularly this sound and imagery and their brave and bold usage that make Halsey a successful can-do girl. The biography on her official website reads as following: "I am Halsey. I will never be anything but honest. I write songs about sex and being sad" (Halsey. – BIO). It is her vulnerability and straightforwardness that make her relatable and popular with fans; being a demonstrative combination of the two archetypes, her art has something to offer for both can-do and at-risk audiences.

"We are the new Americana

High on legal Marijuana

Raised on Biggie and Nirvana

We are the new Americana"

(Halsey. – "New Americana")

2. THE ORIGINS AND ORIGINATION OF HALSEY – EXAMINING THE BACKGROUND

2.1 Standing In-between

"Halsey is an anagram of my first name Ashley, and it’s also a street in Brooklyn where I spent a lotta’ time growing up. [ . . . ] And that’s where I kind of decided I wanted to be a musician [sic]" (Vevo. Halsey – dscvr Interview). Not fitting into the categorized images and traditional, clear-cut genres of the music industry, it is very likely that her uniqueness and complexity as an artist lies in her background. At age seven, she began reading Lolitaand The Great Gatsby – not the most typical bedtime stories for seven-year-olds, – and at age fourteen, she started uploading videos to youtube (Martins). Her fame grew out of a personal blog on tumblr.com, after she put out her first song, Ghost (Robinson). She had an online fan base built on pure charisma well before she signed a record deal, without the interference of the industry; it is not her priority to fit the formulas or fill the patterns of marketing:

I don’t want to be an artist where you can sum up my life’s work in a clickbait sentence. [ . . . ] I don’t want to be Halsey the anything, I’m more multidimensional than that. [ . . . ] It’s unfair to me, to myself, to let people pick apart the dimensions that make me who I am. (Robinson)

To grasp the very foundation of her multilayered artistic persona, it is essential to examine her upbringing. She describes herself as a former –"unconventional child" that came to be an "inconvenient woman" (Martins). As she explains in an interview for Vevo:

I had a little bit a… different upbringing than most kids. My parents had me when they were really young. I have a black dad and a white mom. My father used to listen to Biggie and Slick Rick and Bone Thugs-n-Harmony and Tupac and my mom was listening to The Cure and Alanis Morissette and Nirvana. The eclectic influence that I had growing up definitely affected me and has made it quite an interesting and open and organic process so far. Just taking music I like and making it a reflection of me [sic]. (Vevo. Halsey – dscvr Interview)

Her parents had rather different tastes in music, exposing her to various influences from the beats of hip-hop culture to the heavy choruses of alternative rock which thus aided in the formation of her own individual style. "I just wanna do something that’s not contrived. I mean I love pop music and I wanna make pop music that’s a little bit left off center and has dignity and crosses gender barriers and talks about things that otherwise would be considered un-ladylike [sic]" (Vevo. Halsey – dscvr Interview). In a recent Rolling Stone interview she explains that music is cyclical, and in 2016 genre is "just absolute bullshit." Her music is described as "[ . . . ] too dark for pop, too pop for alternative, [ . . . ] a record that doesn’t fit in" (Hiatt).

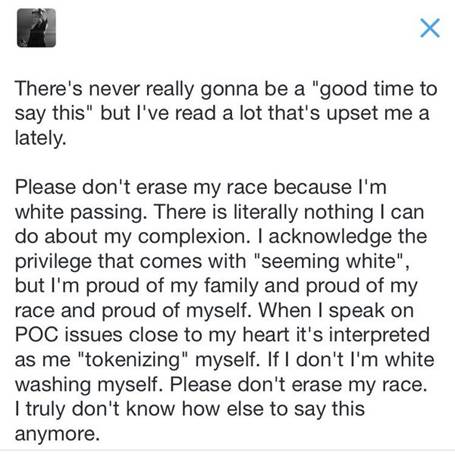

One of the controversial issues surrounding Halsey is her race. As a biracial performer, Halsey represents women of mixed ethnicities, standing as a role model for young girls of different origins and cultures, yet she faces harsh criticism for her actions for these communities. On 28 Jul 2015, she tweeted the following picture:

Figure 3. Halsey addressing her critics. Photo: Halsey (2015).

In a personal essay, mixed-race novelist Rilla Askew discusses that "passing," although most often associated with racial passing, can stand for passing for an economic class or a different sexual orientation. To explain; passing is displaying the aspects of one’s personality that comply to whichever norms the individual is surrounded by, and, repressing those which do not fit the surroundings, "passing toward cultural dominance" (Askew).

People of colour have to fight a constant battle to find valid forms of self-expression, and they are in a never ending search to find sufficient representation in the mainstream culture. Being a mixed race artist with a fair complexion can easily make someone the target of hatred and false accusations about exploiting the very ethnicity he or she was born into. Passing for white makes Halsey victim of biased preconceptions. "I’m mixed race [ . . . ] and I’m very pale. Growing up there weren’t a lot of mixed people in the media who were as pale as I was", explains Halsey in an interview for Elle. On the other hand, she stands as a role model for girls who are also mixed race – who have not had this kind of representation before. "I always felt like I was too light to identify with anyone else. I now have girls reach out to me all the time and say, ‘I’m mixed race like you and I’m just as white as you are. Thank you for being that for me" (Harman). There is a notable "in-between-ness" about Halsey; her bisexuality borders heterosexual and homosexual, her androgyny mixes feminine and masculine, her race is neither distinctly white nor black, her music does not fit into traditional genres. She calls herself the in-between role model; a role model for a lot of different types, and she likes being that. Interviewer Justine Harman mentions the recurring theme of the ‘inconvenient woman’ apparent in Halsey’s music, to which she replies that she identifies as ‘the inconvenient woman’.

She also opens up about her bipolar disorder and her relationship with her family, and how these factors contributed to her artistic persona. She talks about her mother – who is also diagnosed bipolar – with admiration, as an example of how to be strong, bold, confident, and different. Struggling with her bipolar disorder, and how it made her feel and comprehend much more of the world around her than other children in her age group, she had to adapt to and accept these deep feelings – and her mother boldly encouraged her to do so. When, as a young girl she said she would rather be naive and would prefer to worry about her prom dress or her math homework like everyone else her age, her mother asked in reply: ‘Would you rather be blissfully ignorant or would you rather be pained and aware?’ (Harman). Being aware and in pain because of sensitivity can be interpreted as a mark of the artist figure.

2.2 Outdated Media Depictions – An Androgynous Answer

Since the nineteenth century, every generation has had to deal with its own version of the beauty myth – claims Naomi Wolf in The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are used Against Women. This myth, as Wolf explains, is the concept – based on natural selection – that ‘beauty’ as a universal quality, exists objectively. The beauty myth defines women as those who embody beauty, and men as those who possess beauty by possessing women. In reality, the myth is "[ . . . ] a currency system like the gold standard" built to keep male supremacy intact (11-12). Wolf states that it is a fabrication "of emotional distance, politics, finance, and sexual repression. The beauty myth is not about women at all. It is about men’s institutions and institutional power" (13). As a bisexual and often choosing to appear as an androgynous female individual, Halsey struggles against the traditional heteronormative beauty and gender portrayals – she obscures and reverses them. She is biracial, bisexual and bipolar; thus, she is labelled "tri-bi". In the Rolling Stone interview with Brian Hiatt, she expresses her disapproval of the label, which she finds trivializing. She also addresses biphobia and society’s refusal to accept bisexuality as a legitimate sexual orientation (Hiatt).

Her apparent androgyny and bisexuality make Halsey an unconventional female figure in the line of contemporary beauty portrayals – as there is still a lingering misogyny and queerphobia in the media, which had a part in assigning men and women separate roles (Carter 370), and considering any alteration or weakening of borders as a threat to the established system. In "Andro-phobia?: When Gender Queer is too Queer for L Word Audiences," Rebecca Kern defines ‘queer’ as a gendered ‘otherness’ of all non-normative gender identities – in the queer community, gender is expected to be seen as a fluid construct. Kern explains that androgynous people fall outside of the gender binary avoiding gender definition as they identify neither culturally, physically, or physiologically as distinctly male or female; thus, androgyny provides the safety net of dichotomies that patriarchal society needs (242-244). Androgyny and the female masquerade (explained below) share the motif of blending, of multilayered identities, of dissociation from cultural markers. Reynolds defines the masquerade as a tradition that works within culture; performers like Madonna or Annie Lennox, toying with depictions of the feminine, play with various identities to reinvent themselves (289). Halsey goes against the contemporary beauty myth by following the tradition of reinventing the self: just like Patti Smith created a feminised version of living-on-the edge rock ‘ n ‘ roll, seeing herself as a female Messiah (Reynolds 237), Halsey created an artistic persona whilst embracing her androgyny, being a strong supporter of gender fluidity and exceeding the classifications of music genres. During the era of Patti Smith, the process was about reimagining male examples and creating female alternatives, but as of the present day, this process had shifted towards the playful mixing of the male and the female – going beyond the limitations of plain feminine or masculine, pop or alternative, and exploring the endless layers and options that the scale of gender-fluidity offers, whilst triggering a changed representation of queer and androgynous. As Kern claims, "gender ambiguity is not only the ultimate subversion to the male/female dichotomy but also to the heterosexual/homosexual dichotomy" (242).

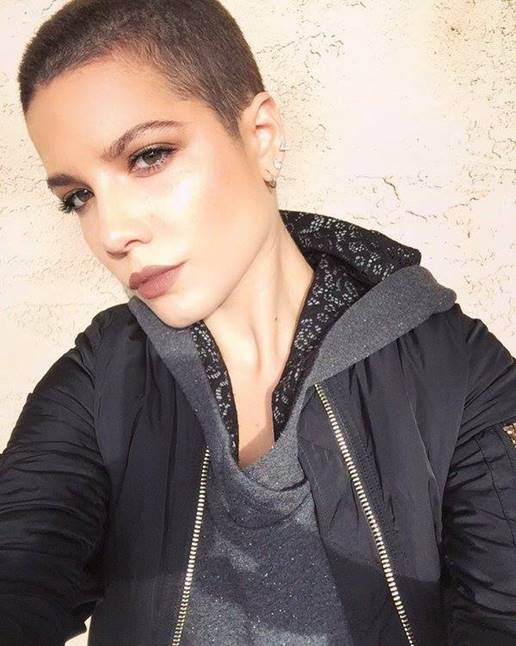

Figure 4. Halsey with a buzz cut. Photo: Halsey (2015).

Halsey transgresses the gender binary, as she does not let classifications of sex and gender affect her individual style, thus aiding the formation of changed media attitudes that favour the non-normative. The image above shows Halsey with a buzz cut, rather tomboyish, leisure clothes, and it is important to note that both her everyday and stage clothes range from androgynous, unisex ones to glamour diva. On Figure 5, she wears a fullcap, an Adidas tee-shirt and sweatpants, and velcro sneakers, seeming rather boyish, crouching, looking sporty and leisure, her skin covered up to her neck.

Figure 5. Halsey in leisure clothing. Photo: Halsey (2016).

Figure 6. Halsey on stage. Photo: Halsey (2016).

On Figure 6, she performs in a blue faux-fur coat, a see-through fishnet crop top, a white bra, and jeans hot pants – an outfit that can be considered provocative, showing a lot of her skin, making her look very sexual. The faux-fur adds to the diva image.

Halsey names fashion designer, artist and photographer Karl Lagerfeld as the most prominent inspiration to unleash her androgynous self – she has recently posted a photo on her official instagram account, posing with Lagerfeld, with the following caption: "The most inspiring moment of my life to date. I cannot credit my drive to pursue the exploration of my androgyny to any other human being. The juxtaposition of the ultra feminine and the andro [ . . . ] (Halsey). On Figure 7, Halsey, with an androgynous short haircut, wears white panties and a tee-shirt that reads: ‘‘RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY’ – wearing the statement and showing her legs make the photograph a strong protest against the gendered objectification of female bodies, as she is not sexualised or objectified despite wearing only panties. Halsey explains that 2016 is "an incredible time for fashion and a socially aware narrative." She takes note that this generation accepts gender fluidity – a tremendously powerful thing for people to embrace. "If you have less expectations of gender, you know, you have less . . . less reason to judge people. And any less reason to judge people is a step in the right direction for human rights and the human race." Regardless how rigidly the media converses the traditional dual roles of gender, Halsey believes that this generation accepted gender fluidity, walking towards a more accepting society where less people are judged for being different (Billboard).

Figure 7. Halsey in a tee-shirt that reads: ‘RAISE BOYS AND GIRLS THE SAME WAY’ Photo: Halsey (2015).

"I’m headed straight for the castle

They’ve got the kingdom locked up

And there’s an old man sitting on the throne that’s saying

I should probably keep my pretty mouth shut"

(Halsey. – "Castle")

3. HALSEY’S ARTISTIC MISSION AND POST-FEMINIST ATTITUDE

3.1 From Concept Record to Immortalization

Halsey’s debut album, Badlands, grew out of her fascination with hotel rooms as isolated spaces– states interviewer Chris Martins, who describes the record as a "larger-than-life vision" which "combines the synthy darkness of Lorde, the neon-pop chutzpah of Miley Cyrus and the flickering film noir of Lana Del Rey". Badlands, set fifty to hundred years in the future (Robinson), and described by Halsey as a dystopia in a parallel universe, a post-apocalyptic civilization, is also a metaphor of her inner turmoil: "There’s a booming, rotating, never sleeping city in the center of my brain and no body [sic] can come in and I can’t escape. [ . . . ] That realization was really heavy for me but also strangely therapeutic in terms of coping with my own isolation and the way my life was changing" (Weatherby). The album’s opening track, "Castle" was inspired by Halsey’s personal experiences with the music industry – the "old man sitting on the throne" representing the patriarch (Graves).

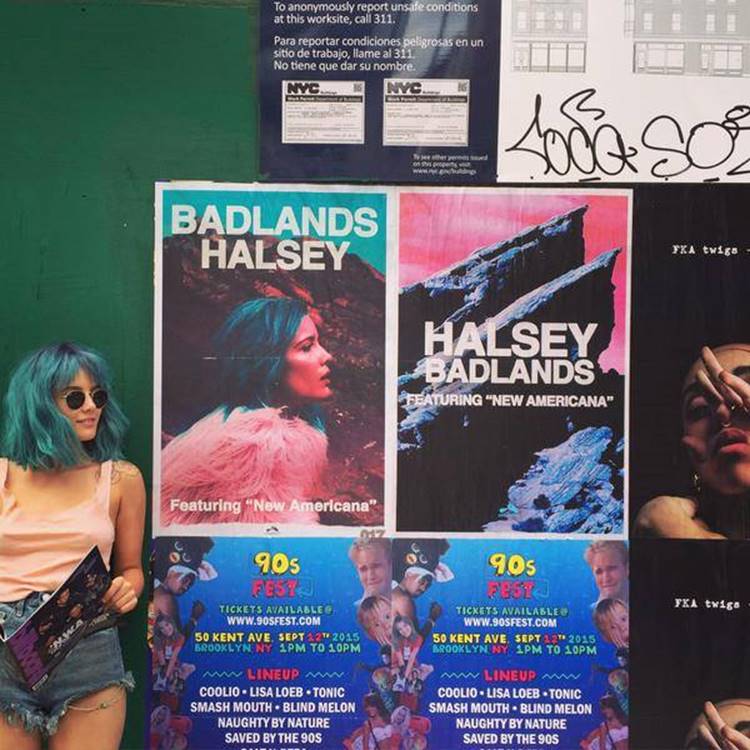

Figure 8. Halsey next to Badlands Posters. Photo: Halsey (2015).

The lyrics illustrate how female performers are objectified by the media: "Sick of all these people talking, sick of all these noise/ Tired of all these cameras flashing, sick of being poised" (Halsey. – "Castle") The song starts with voicing a tiredness, an exhaustion from presumptions and inequality, then shifts to describing how social and cultural pressures create a torn identity that is completely aware of being objectified, and seeks masochistic pleasure as a way of coping with that – the mock-begging suggests that the singer wants to take control of her situation by instructing those who initially objectified her. "Now my neck is open wide, begging for a fist around it/ Already choking on my pride, so there’s no use crying about it" (Halsey. – "Castle"). The whole album revolves around motifs of self-expression, pain, coping, sexuality, sadness, anger, and control, expressed via bold, honest lyrics. Although she wrote every song on guitar, the instrument is not included on the tracks – as Halsey wanted to achieve a futuristic vibe (Hiatt). As a possible synopsis of the record, Halsey names "Gasoline," a track she wrote and produced on the day the album was due, so her label featured it on the deluxe edition (Robinson). "Gasoline" is a dark song about carrying a flaw that makes one essentially different from others: "I think there’s a flaw in my code/ These voices won’t leave me alone".

The creation of Badlands, her first album, is part of Halsey’s much greater artistic destination of immortalization – Badlands stands as a landmark in the journey to immortality, she regards it as the starting point. In an interview for Pop Crush, Halsey explains that her ultimate artistic goal is to immortalize herself through her music. She names Amy Winehouse as a significant inspiration, as a person who embodied music that is honest and romantic, in an unpolished, unashamed, unapologetic way. For Halsey, immortalizing herself means taking her demons and using them to live forever, by writing about them, and thus, postponing her second death. She believes that Amy Winehouse executed that nearly perfectly (Pop Crush). Alongside building a legacy, Halsey aims to have an impact on mainstream media as well – talking with Peter Robinson, she comments that she considers her artistry an "entry point" in showing that young audiences know more and have a bigger impact than the mainstream presumes, explaining that opinions of the media are irrelevant, yet, her "presence in it is important."

Halsey’s personal aim intertwines with her social aim, as whilst immortalizing herself through her artistry and staying true to what she calls her authentic self, she incorporates a peculiar ‘otherness’ into the mainstream, lifting the ‘other’ to a higher level, raising awareness, provoking conversation and calling for change. Her music is genre- and lyrics-wise so multi-dimensional that the industry is scared of her, and the masses greet her with questioning faces, in her own words:

[. . .] I’m playing to conservative America like, ‘is she gay? I don’t get it. She’s singing about guys but she looks like a lesbian’. I’ve got this song that’s about how this new generation’s accepting of diversity, accepting of different walks of life etcetera. No one fucking understands it. (Robinson)

She approaches the mainstream in a valiant, unapologetic, heart-felt way – embracing and utilising her imparity. She believes that her approach to her fanbase is much more authentic than that of the artists controlled by the industry – therefore she considers unfiltered communication as a major foundation of her relationship with her fans. She explains that she strives to be "calculated in an organic way," using social media as a platform for calculated communication, in her own words, rather than for fabricated promotion; her marketing strategy is to present her most organic self to her fans (Robinson). Her personal and social objectives get combined in her artistry – her route to immortalization starts with the creation of her artistic persona, continues with the birth of the concept album, Badlands, and achieving the position she currently holds in the mainstream – on the one hand, she stands as a representation for several layers of society, such as queer people or mixed ethnicities, and on the other hand, she fulfills her personal aims.

3.2 Post-feminism – Halsey as the Contemporary Rebel

The bold, shameless approach which Halsey takes in the flashy provocation and constant challenging of the media links to post-feminist contexts and discussions. Rosalind Gill explains in her essay titled "Postfeminist media culture: elements of a sensibility," that postfeminism is a contradictory notion, as there are still arguments about whether the term is to denote a theoretical approach, a new feminist movement after the Second Wave or a regressive position (147-148). Postfeminism does not fit into a box, it is a concept of in-betweens and overlapping categories, just like Halsey – as discussed in Chapter Two. Simon Reynolds examines in "What a Drag: Post-feminism and Pop" that the term ‘post-feminism’ first appeared in the mid-eighties, to designate a new wave of feminism that differs from old feminist agendas– focussing on media representation. Postfeminism is described as generally more playful and ironic, and inspects feminist issues from new perspectives. ‘Post’ marks the option of reclaiming concepts of femininity which feminism wrecked, of taking subordinations and transforming them into affirmations (317-318). Halsey embraces irony and the postfeminist sensibility, and by subversion, follows the strategies of New Pop, or "pop deconstruction," as defined by Simon Reynolds, who explains how Scritti Politti made attempts to deconstruct pop’s discourse and "celebrated the idea that there is no truth, only language." According to Reynolds, Scritti, Annie Lennox and Clare Grogan were among the few of those who took up New Pop (316-317). Inter alia, Halsey claims that women should reclaim the word ‘sexy’, as it has become a concept seen from a male perspective - that women should have autonomy over their bodies and sexuality (Graves). She also voices her disapproval of the beauty standard of thinness, calls body shaming a "toxic mentality in society" and compares the resulting privilege of it to white privilege (Graves). Halsey’s feminism is unplanned and unbound by preconceptions – she describes her aspirations as follows:

My goal isn’t to write about feminism: it’s to write about my life. I’m not catering to anything or think about a message. The fact that I’m a female artist and am 20 years old, I need to write music that is honest but not vulgar and doesn’t victimize. That alone makes me a bit of a feminist artist. (Kohn)

Having shot two separate videos for her single "Ghost," one depicting a heterosexual affair, another a homosexual one, Halsey challenged the doulbe standard regarding portrayals of male-female versus female-female romance and sexuality (HalseyVEVO. Ghost [Room 93 Version]; Ghost). In an interview for FADER she explains that out of the two videos, the one with a male lead actually has more sexual content: "There was [sic] fucking nails scratching down backs and like orgasm faces and being thrown up on a desk by my thighs and everyone was like oh what a great love story, this is like nineties love." The video with a female lead got mixed reviews and critics tagged it as controversial, provocative and pornographic, despite featuring less sexually explicit material. Halsey voices her disapproval of the media portraying female-female relationships as pornographic, and explains that challenging this misconception was precisely the reason why she made the two videos (The FADER. Halsey – Everything You Need To Know). Halsey toys with different kinds of sexual representation and she purposefully shocks and scandalizes in order to get people involved in the conversation. In "Queer (Post)Feminism," a chapter from the comprehensive postfeminist study Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories, Stéphanie Genz and Benjamin A. Baron discuss that feminism and queer theory both aim to "deconstruct identitiy categories and register difference", and that queer theory attempts to break down the essentialist and to replace it with the contingent (in parallel to post-feminism, as explained above) (124-125). As illustrated by the analysis of her lyrics, visual representations and interviews, the rebel persona of Halsey can be regarded as a figure combining postfeminism and queer theory. She repeatedly states her opinion on various postfeminist and queer issues, in an honest and uncalculated manner. Interviewed by Shahlin Graves, Halsey agrees that "there’s a double-standard in the music industry that works against female artists being able to portray themselves romantically or sexually, without being objectified or over-sexualised." She adds that she grew up idolising Mick Jagger and other male artists and performers who were sexual on stage. Halsey attempts to adapt this type of sexuality and normalize it as a female musician, battling the double standards of mainstream culture and media. Criticism only adds fire to her ambitions, as her ultimate goal is to own her sexuality both in her private life and on stage as a performer too, so the media cannot distort it (see the discussion on Figure 1 and 2 in Chapter one). "If I can own that fact then I can own the sexual nature of myself, then no-one can objectify me because it’s in my power, it’s in my hands," Halsey declared (Graves). Her approach can be regarded as idealistic, yet, her conflict with media-made representations of herself, and her engagement to affect them stand as major marks in the progress towards a media that offers more varied and less rigid roles to the female artist.

"We’re the underdogs in this world alone

I’m a believer, got a fever running through my bones.

We’re the alley cats and they can throw their stones

They can break our hearts, they won’t take our souls."

(Halsey. - "Empty Gold")

CONCLUSION

This thesis set out to explore the artistic persona of the contemporary provocateur, Halsey, and has identified her resources and modes of fighting the mainstream media and its outdated depictions of sexuality and gender. An in-depth investigation into her origins and current positioning resulted in recognizing her as an in-between role model representing LGBT, POC and gender issues while personifying the ‘other’ and incorporating it into the mainstream. The study used various interviews, audio recordings, articles, essays and visuals, exploring the diversity Halsey embodies by being a mixed race, bipolar and bisexual individual, who plays with gendered identities, utilizing unisex, androgynous and even deeply sexual and sensual attributes, thus provoking generalizing media portrayals and attacking the gender binary. Her character and modes of evoking change were traced back to several antecedents in the music industry, highlighting parallels between her and other female rebels, ultimately concluding that she can be regarded as a postfeminist who toys with different representations, genres, imagery and lyrical dimensions to initiate change in the gender dichotomy present in the media. Her presence, however new, is a major, unapologetic entry point in the formation of a less limiting, less misogynist, less queer-o-phobic media.

Works Cited

- Askew, Rilla. "Passing: The Writer’s Skin and the Authentic Self." Personal Essay. World Literature Today. July 2009. Web. 20. March. 2016.

- Billboard. “Halsey: ‘This Generation Accepts Gender Fluidity.‘” Online video clip. Billboard, 10. March. 2016. Web. 25. March. 2016.

- Carter, Cynthia. "Sex/Gender and the Media: From Sex Roles to Social Construction and Beyond." The Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Media. Ed. Karen Ross. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. Print.

- Coscarelli, Joe. Halsey, With ‘Badlands,’ Is Moving Fast to Share a Secret Language. www.nytimes.com. The New York Times, 5. Aug. 2015. Web. 11. March. 2016.

- Genz, Stéphanie, and Benjamin A. Brabon. "Queer (Post)Feminism." Postfeminism: Cultural Texts and Theories. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009. Print.

- Gill, Rosalind. Postfeminist media culture: elements of a sensibility. European Journal of Cultural Studies. ecs.sagepub.com. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore: SAGE Publications,. May 2007 vol. 10 no. 2. 147-166. Web. Apr. 03. 2016.

- Graves, Shahlin. "Interview: Halsey on Her Debut Album, ‘Badlands’." www.coupdemainmagazine.com. Coup De Main, 16. July. 2015. Web. 28. March. 2016.

- Halsey, (halsey). "I’ve been thinking about this so much and I haven’t been able to find the right words or platform or time but." July. 28. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. 2016. Tweet.

- Halsey. "Lottie – Makeup Artist is my favorite makeup-er 💕🐱💕." Facebook. Dec. 11. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. Photo.

- <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1459631790./550771511764591/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. " Outtake from NYLON." Facebook. 03. Sept. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1459029207./518721674969575/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. "Castle." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Colors pt. II." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Colors." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Coming Down." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Drive." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Empty Gold." Astralwerks, 2014. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Gasoline". Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Ghost." Astralwerks, 2014. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Haunting." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Hold Me Down." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Hurricane." Astralwerks, 2014. Digital download.

- Halsey. "I Walk The Line." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Incognito." Facebook. 21. Aug. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1459192219./513591068815969/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. "New Americana." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Roman Holiday". Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Strange Love." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. "Trouble." Astralwerks, 2014. Digital download.

- Halsey. "👽👽👽." Facebook. 18. June. 2015. Web. Mar. 28. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1459029357./486684778173265/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. BIO. iamhalsey.com. Web. 12. Mar. 2016.

- Halsey. Control. Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- Halsey. (iamhalsey). "The most inspiring moment of my life to date. I cannot credit my drive to pursue the exploration of my androgyny to any other human being. The juxtaposition of the ultra feminine and the andro. A legend. Sorry I’ll keep going…….

chanelofficialkarllagerfeld #frontrowonly." Instagram. 8. Mar. 2016. Web. 28. Mar. - Halsey. No Title. Facebook. 02. Oct. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1459029207./528838743957868/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. No Title. Facebook. 03. Mar. 2016. Web. 08. Apr. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1460132865./585788401596235/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. No Title. Facebook. 13. Mar. 2016. Web. 08. Apr. Photo. <https://www.facebook.com/HalseyMusic/photos/pb.253431031498642.-2207520000.1460132861./589944911180584/?type=3&theater>

- Halsey. "Young God." Astralwerks, 2015. Digital download.

- HalseyVEVO. Halsey – Ghost. Online video clip. Youtube. 11. Jun. 2015. Web. 28. Mar. 2016.

- HalseyVEVO. Halsey – Ghost (Room 93 Version). Online video clip. Youtube. 27. Oct. 2014. Web. 28. Mar. 2016.

- Harman, Justine. "Halsey Opens Up About Being a Reluctant Role Model." www.elle.com/. Elle, 27 May 2015. Web. 14. March. 2016.

- Hiatt, Biran. "Halsey on Duetting With Bieber, Hating ‘Tri-Bi’ Label." www.rollingstone.com/. Rolling Stone, 10. Feb. 2016. Web. 11. March. 2016.

- Kern, Rebecca. "Andro-phobia?: When Gender Queer is too Queer for L Word Audiences." The Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Media. Ed. Karen Ross. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. Print.

- Kohn, Daniel. "The PV Q&A: Halsey on Her Feminist Persona." Http://www.purevolume.com/. PureVolume, 21 Jan. 2015. Web. 27. March. 2016.

- Martins, Chris. "Art-Pop Singer Halsey on Being Bipolar, Bisexual and an ‘Inconvenient Woman’." www.billboard.com/. Billboard, 21 Aug. 2015. Web. 27. Mar. 2016.

- Pop Crush. "Halsey on Being A Female Artist, Amy Winehouse & Her Fans." Online video clip. Youtube, 13 Aug. 2015. Web. 28. March. 2016.

- Projansky, Sarah. Spectacular Girls: Media Fascination and Celebrity Culture. New York: New York UP, 2014.

- Reynolds, Simon, and Joy Press. The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion, and Rock ‘n’ Roll. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1995. Print.

- Robinson, Peter. HALSEY INTERVIEW: "I DON’T BELIEVE PEOPLE WHO SAY THEY’RE THEMSELVES ALL THE TIME." popjustice.com. Pop Justice, 5 Nov. 2015. Web. 28. March. 2016.

- Rolo, Charles. "Lolita, by Vladimir Nabokov: A review by Charles Rolo." The Atlantic Monthly, Sept. 1958. Web. 02. April. 2016.

- The FADER. "Halsey – Everything You Need To Know." Online video clip. YouTube, 15. Aug. 2015. Web. 13. March. 2016.

- Trier-Bieniek, Adrienne M. and Patricia Leavy. "Introduction to Gender & Pop Culture" Gender & Pop Culture: A Text-reader. Rotterdam: Sense, 2014. Print.

- Valdivia, Angharad N. "Feminist Media Studies in a Global Setting: Beyond Binary Contradictions and Into Multicultural Spectrums." Feminism, Multiculturalism, and the Media – Global Diversities. Sage Publications, 1995. Print.

- Vevo. Halsey – dscvr Interview. Online video clip. YouTube, 19 Jan. 2015. Web. 12. March. 2016.

- Weatherby, Lea. "Halsey’s Uncharted Territory." www.interviewmagazine.com/. Interview Magazine, 31 Aug. 2015. Web. 28. March. 2016.

- Wolf, Naomi. The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women. New York: W. Morrow, 1991. Print.